The Port Phillip and Western Port region is home to more than five million people and includes all of urban Melbourne, growth centres on the urban fringe, highly productive farming land, forested parks and ranges, and a network of rivers, wetlands and estuaries which flow to our two valuable bays – Port Phillip Bay and Western Port.

The region supports a range of non-urban land uses located on or near the urban fringe that are critical to the functioning of urban Melbourne. These include tourism, airports, water treatment plants, extractive industries, waste and resource recovery operations and renewable energy infrastructure. It is important to ensure these uses are located in areas that have as little impact as possible on biodiversity and other natural and cultural values.

The Port Phillip and Westernport region faces numerous complex challenges including climate change, increasing urbanisation, population growth, land use pressures and loss of biodiversity

20,000 years ago

Caring for Country for tens of thousands of years

Imagine you could go back 20,000 years and visit this region during the time it was home only to the Kulin Nation Peoples.

You would see a region holding evidence of 500 million years of the Earth’s history in its rocks and fossils. A landscape formed by ancient sedimentation in deep ocean and shallow marine environments, massive continental shifting and spectacular volcanic activity. Some 100 million years earlier, the area was part of a giant continent that included Antarctica. And now, you could still walk south across a vast exposed plain to the area later known as Tasmania.

If you could speak the language of the Indigenous Aboriginal People, you might learn that their Ancestors have been in this area for many thousands of years and were here when the last volcanoes erupted.

You won’t see first-hand any of the enormous herbivorous mammals called diprotodons that browsed in this land for grasses, fruit and leaves, because they became extinct perhaps another 20,000 years earlier. But you could hear of them in stories told by Aboriginal Elders that have been passed on through the countless generations.

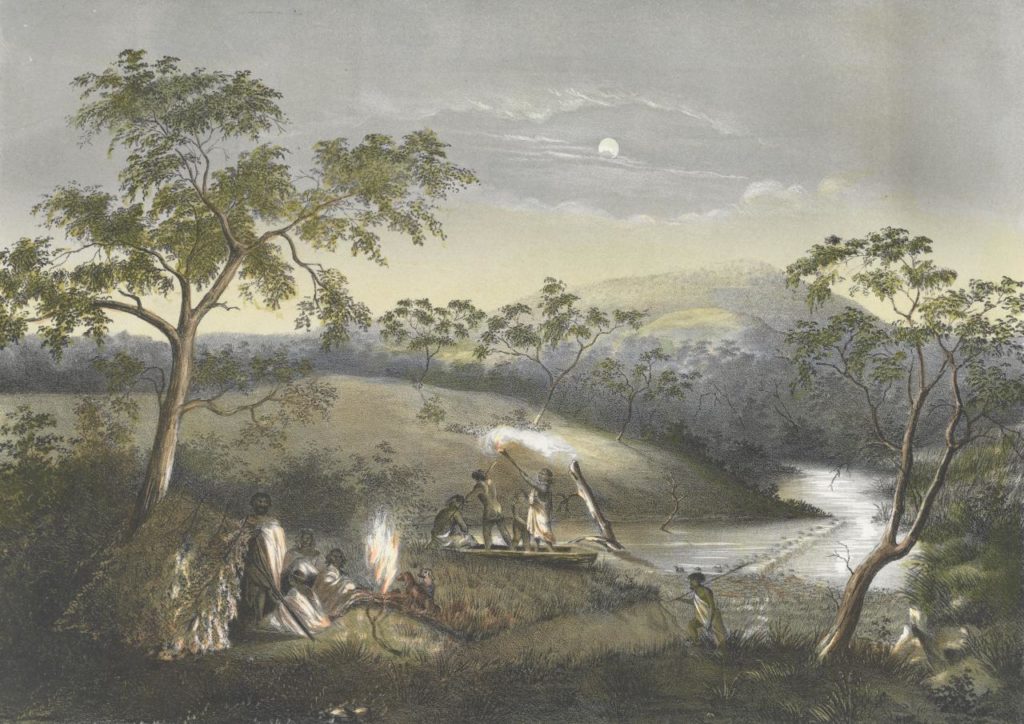

They may also tell of the dreamtime and their creator and spiritual leader Bunjil the great eagle. And they might share important lessons about the seasons, sustainable food sources and hunting techniques that have sustained their People for millenia, such as trapping eels in the waterways, hunting kangaroos, collecting shellfish from shallow marine areas and gathering murnong yam daisy on the dry plains and lily bulbs at the edges of large swamps.

You might see groups of one or two Families collecting food and other materials locally, periodically moving to other areas and allowing former locations to regenerate. In daily life and at various parts of the landscape, you might see structures such as stone eel traps, hunting and cutting tools such as woven fish traps and axe stones, gathering implements such as woven baskets and clear signs of gathering and eating places such as shell middens.

Some of the lessons and practices are recorded in paintings while many more are passed on as teaching stories, songs and dances from generation to generation.

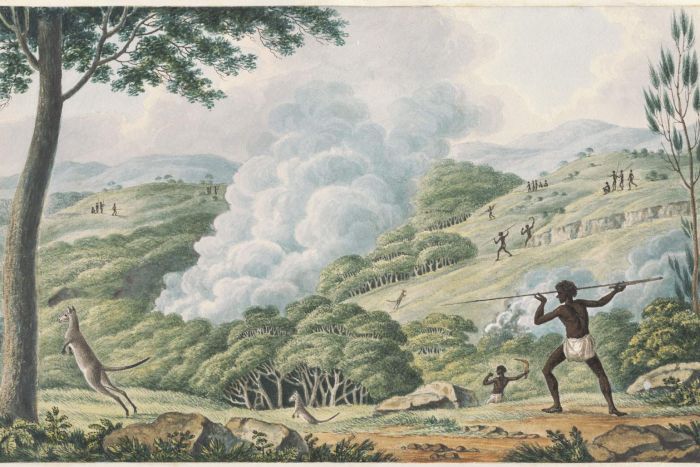

You would see that the Kulin Nations People actively manage the area’s natural resources for productive purposes. For example, extensive use of fire on the volcanic plains keeps the plains largely grassy and productive for hunting. However, you quickly understand that Aboriginal cultural and management practices are in harmony with the regional environment and its sustainability.

The total Aboriginal population of the region is probably in the thousands. You would learn that some sites are important meeting places and that ceremonies involving several clans are performed here often and for many reasons, bringing people together from near and far. Trading between clans and nations also occurs, evidenced by axe stones that were shaped at a site many weeks’ travel away.

By understanding their history and seeing the way they manage the land, you would conclude that their use of this Country is in balance with its ability to regenerate.

But more than that, there is the deepest and strongest of bonds between the People and their land, a spiritual connection of love and respect, a caring for this Country developed through long ancestry. Kulin Nations People are part of the Country and the Country is part of them. It always was and always will be.

200 years ago

The onset of colonisation

Now imagine you could see this region around the start of the 1800s, at the time British colonisation was spreading across Australia and the Aboriginal stewardship of this land, which had evolved and flourished over many thousands of years, was being abruptly, and often violently, ended.

You will see two neighbouring yet visibly different bays. The larger, called Nerm, Nairm or Narm-narm by the Kulin Nation People and later known as Port Phillip Bay, might have pods of dolphins and a small family of whales playing at the surface of its deep blue water. The smaller bay to the east, called Berbinangery and ironically later known as Western Port, has deep channels but is generally shallower. It features lush seagrass meadows and large inter-tidal zones daily exposing mudflats and mangroves, together supporting a vibrant array of marine and birdlife.

Visible in the north and east are mountain ranges comprised of uplifted sedimentary rocks, basalts and exposed granites. In the west is a vast basalt plain. Along the coastal areas you would see rivers and streams flowing to large freshwater swamps before entering the bays and then the sea.

Surveying the region from west to east you would find a waterway called Wirribi-yaluk and later known as the Werribee River. It rises in uplifted sedimentary hills in moist forests then travels east through dry forests and woodlands. It meanders across the grassy volcanic plains then turns south past an impressive granite outcrop and on to Port Phillip Bay among coastal scrubs. You may still see see first hand the effects on the plains of Aboriginal fire stick farming. Emus, dingoes and mobs of kangaroos and wallabies are attracted to the fresh shoots of grass.

Moving east you would find another major waterway, the Mirrangbamuran that is later named the Maribyrnong River. It rises in moist forests before flowing south through dry forests, woodlands and grasslands. The riverside is typically forested, providing sheltered habitat for the reclusive platypus, an animal the likes of which are not found on any other continent in the world, and a range of native freshwater fish species.

The Maribyrnong River merges near Port Phillip Bay with the region’s biggest waterway, the Birrarung that will become known as the Yarra River. It originates in uplifted sedimentary rocks and volcanic outcrops some 120 kilometres to the east of its mouth to the bay. It rises in moist mountain forests and passes through a mixture of dry forest and grassy woodland. This prolific and often dense native vegetation is home to a diversity of flora and fauna species including orchids, parrots, eagles and eastern quolls. The topography flattens as the river journeys south-west through sandstones deposited when this land was the floor of an ocean many million years ago.

Heading south-east you find a major stream rising in extinct volcanic hills called Korranwarrabul and later known as the Dandenong Ranges before quickly dropping to inland and coastal plains as it heads west and flows into a large freshwater wetland. The upper reaches of this stream, known as Dandinnong or the Dandenong Creek, are vegetated with dry forest while lower down the wetland is surrounded by swamp scrub amid a plain of lowland forest. The wetland is one of a series in the coastal areas of the region and is a hub of native birdlife feeding, nesting and resting en route to destinations elsewhere around the globe.

Further to the south and east you find a series of rivers and streams that rise in the surrounding hills and ranges and flow to Western Port. The higher areas generally have moist forests with most of the waterways meandering over plains before entering a vast swamp, that slows and filters the water before it drains to Western Port. In the slopes and valleys of Nurlmoolak, later known as the Bass Hills, are impressive tall wet forests. Vegetation in the lower areas of the catchment includes woodland, swamp scrub, coastal scrub, grassland and mangroves which together provide habitat for native fauna including wombats, kangaroos, wallabies, emus, snakes and extensive birdlife. Abundant whiting are found in the seagrass beds of Western Port.

Across the region, you would find several sites that could produce rock and minerals to aid building and construction. By understanding the geology of the region, you could surmise that there would be underground layers of ancient sands and gravels that act as aquifers and could yield groundwater. By studying the various surface soil types across the region, you would note the opportunity for a variety of introduced and productive food crops which could help feed the population of the new settlement that is being planned.

Now

The Port Phillip and Western Port region today

Now consider a tour of this region in our modern times. Perhaps you begin by cruising through the Port Phillip Bay heads aboard a luxurious passenger ferry and making your way to the docks at the northern shore. Your spirits will be high if some playful dolphins, still common in the bay, have been frolicking in the bow wave.

Little has changed geologically in the past 200 years and the landscape and distant ranges remains an impressive horizon.

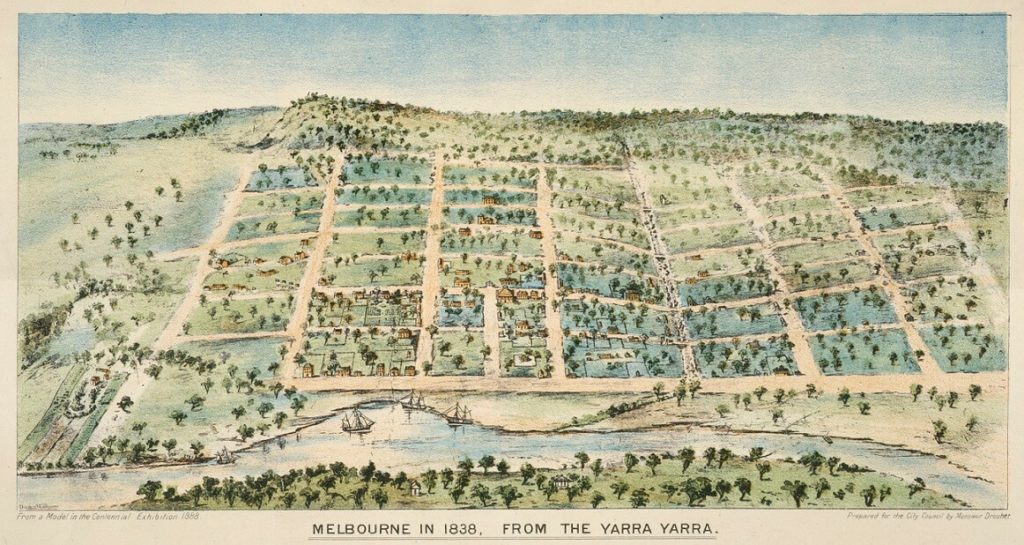

However, you will be aware of the extensive settlement that began in the 1830s and the gold rush of the mid 1800s that saw rapid growth in the Port of Melbourne. Population continued to grow through the 20th century with migration from interstate and overseas.

It is obvious to you that this site on the banks of the Yarra River is still an important meeting place and Melbourne is now a major urban centre. It is the capital city and economic heart of the State of Victoria, a hub of social interaction, entertainment, sporting and cultural activities, a centre of learning and technology with a culture and image well known internationally. It includes health and education precincts including knowledge–based industries of national significance, industrial precincts and transport gateways such as the Port of Melbourne and Melbourne Airport..

You notice as the ferry travels through the bay that urban infrastructure is now an important land use around the region, the most striking feature being the office towers in the metropolitan skyline.

The air is filled with the sound of not hundreds but many thousands of voices with a diversity of origins and cultures. The population of the region has grown to more than 5 million. Evidence of the Aboriginal culture that dominated the region for tens of thousands of years is now far less evident.

The complexity of the technology being used has increased significantly and trade takes place daily not only with adjoining regions but with other countries. This process has given the population greater access to services and material goods. Resources available to people in the region are equal to or greater than most areas in the world. The environment as measured by indicators such as air and water quality is generally good by world standards. Living conditions in the region are of a very high standard and Melbourne has a reputation as one of the world’s most liveable cities.

A flight across the region from west to east clearly illustrates the complex mix of natural and modified ecosystems that co-exist.

Once airborne, you see that the urban area, though a driver of land use and energy flows, occupies only around 14 per cent of the region. About 42 per cent is native vegetation that has not been cleared since European settlement and about 44 per cent is rural farmland.

On closer inspection of the urban and rural areas you notice hundreds of thousands of individual parcels of land illustrating that ownership of land is systematically managed. The urban area is interspersed with many areas of open space and cultural landmarks. Major road systems and rail infrastructure radiate out from the centre of Melbourne, providing important transport links between housing, jobs and services.

Flying over the western catchments of the region, you see that the Werribee and Maribyrnong Rivers still have native forests on significant areas of the ranges at the top of their catchments. It is apparent that some areas are harvested for timber resources.

The flat expanses of the basalt plains, previously native grasslands, are now dominated by some of the industrial heartland of Melbourne, new suburban development and many farming properties. Crossing much of the dryland farming areas are escarpments and deeply eroded waterways. Prominent in the mostly dry farming landscape are two green areas with intense patchwork patterns signifying the use of irrigation near Bacchus Marsh and Werribee.

In the lower Werribee catchment you are shown a substantial waste treatment system that collects and treats most of Melbourne’s sewage. This facility was commissioned in 1897 and has proved to be an initiative of great foresight. It receives the raw sewage through an intricate system of pipes and channels then treats it with world class technology in a large area of ponds and lagoons that eventually produces water of sufficient quality to flow into the bay. While providing an effective and convenient sewerage system for households across the region, this facility doubles as a world-renowned wetland that sustains important wildlife habitat and features numerous rare and threatened species among its avian, terrestrial and aquatic inhabitants.

Moving east into the Yarra catchment you see a green corridor through the suburbs linking the city to the fertile floodplains of the Yarra Valley that is famous for high value agriculture producing wine, beef, vegetables, fruit and flowers. The pilot of your small plane is watchful for hot air balloons cruising through the valley. The balloons are indicative of the strong tourism industry that has been developed in this area over recent decades.

Higher in the Yarra catchment the rich farmland gives way to the foothills and forested highlands of Kinglake plateau and the Yarra Ranges National Park. These are some of the major areas of remnant native vegetation in the State. They include diverse vegetation that provides habitat for species including the helmeted honeyeater and the Leadbeaters possum. Some areas of these extensive forests are also managed for timber production.

The upper reaches of the Yarra catchment also feature a number of huge water storages surrounded by pristine subcatchments that are closed to the public. The “closed catchment” policy for this series of dams results in potable water of very high standard for most of the region’s residents and they are more evidence of remarkable vision by our forebears in designing aspects of Melbourne.

South of the city, you see that the Port Phillip Bay coastline and the Mornington Peninsula are popular recreation and tourist destinations. Grazing enterprises, vineyards, intensive vegetable farming and patches of remnant vegetation are noticeable in the rural areas of the peninsula.

To the south-east of Melbourne, urban development extends through the Dandenong catchment and you can see more sub-divisions and urban development being constructed now as the city spreads further out into the highly productive farmlands in the Western Port catchment.

The Koo Wee Rup area is no longer a massive swamp. It is now cleared of native scrub and protected from constant flooding by an elaborate system of man-made drains, testament to a major engineering effort that opened up this area for agriculture.

Heading east around the shores of Western Port, you notice some of the region’s 12,000 hectares now designated for extraction of minerals used in building and construction. Sand mining around the Grantville area is noticeable and is a reflection of the renowned sandbelt areas that also provide for some of the world’s best golf courses in the southeastern suburbs and on the Mornington Peninsula.

To the north of Western Port you can see the Gembrook and Bunyip Forests providing important remnant vegetation and habitat for native fauna. To the east, the Bass Hills have been largely cleared to enable agriculture, including dairy farming, though you notice substantial new vegetation planted in many gullies and waterways. French Island and Phillip Island, to the south, are major coastal features and include Victoria’s most visited tourist attraction where the little penguins put on a nightly show.

From the air over Western Port, the mangroves, mudflats and saltmarsh on the shores appear healthy in some areas but less so in others, while the muddy waters in the north-east of the bay indicate that the well-known seagrass meadows are in a very poor state. This is a symptom of significant levels of sediments and nutrients that travel through the waterways and into Western Port. Investigations have suggested that the causes include clearing of remnant vegetation, erosion in streams, urban development and nutrient runoff from agriculture.

A similar scenario for water quality is reported in Port Phillip Bay where there are also significant inputs of sediments, nutrients and other pollutants from the intricate urban stormwater system. While stormwater is a contributor to water quality problems, it is an effective system for the management of surface water flow in the urban area and minimises costly flooding across the region. You muse that this is an example of the difficulty in striking a balance between human and environmental needs.

You return to the ground to see some of the stunning natural assets of the region. You confirm that 42 per cent of the total area retains its original vegetation cover. However, several specific vegetation communities such as grasslands have been significantly diminished. Over 50 native flora species and over 70 native fauna species are considered threatened.

It is estimated that 10,000 to 20,000 plant species have been introduced to the region, mainly for food and aesthetic purposes. For example, some trees rare in the wild, such as Eucalyptus crenulata or Buxton gum, are now quite prevalent in urban areas. About 1,000 of these introduced species have now become naturalised and established viable populations. Some species have become established as weeds affecting environmental areas and agricultural production. Serrated tussock, blackberry, ragwort, Paterson’s curse, gorse, boneseed and many other weeds have unfortunately become part of our regional landscapes and require ongoing attention and resources to manage and restrict their further spread.

Several vertebrate and invertebrate fauna species have also been introduced to the region deliberately or accidentally. Rabbits and foxes have been long standing problems with substantial impact on environmental and agricultural values. More recently, populations of deer have become widespread causing significant damage to native vegetation. And the extensive impacts of feral cats on native wildlife has come into sharp focus with these pests being recognised as a priority at national scale.

The native fauna has responded in a variety of ways to the changes that have occurred in the past 200 years. Several species no longer occur in the region outside sanctuaries and zoos, though several exciting government and private sector partnerships and initiatives are in place to breed and reintroduce lost or threatened species to our landscapes including eastern barred bandicoots. Other species, for example Leadbeaters possum, are now limited to particular patches of habitat that can still support them and are therefore very vulnerable to climate change, bushfire, pest predation and other threats.

However, some species have thrived in the new environment, including brushtail and ringtail possums and many species of birds including rainbow lorikeet and red wattlebird. Some native fauna species are also occupying this region for the first time, such as the grey-headed flying fox that is threatened in the northern states but now occupies sites in metropolitan Melbourne.

You reflect that society has enjoyed substantial benefits of the vision shown by our forebears, and is continually adjusting its practices and laws to manage the exploitation of natural resources.

You realise that the region is a centre of many of Victoria’s most important environmental, economic and social assets.

Key features include the agricultural industries that have harnessed innovative technologies to bring unprecedented production and enabled a diverse range of enterprises to occur here. The region remains a major agricultural producer and the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020 and 2021 highlighted the value of local food production in the rural hinterland of Melbourne.

Most of the coastline is public land and accessible every day to everybody. There are wetlands of international importance and remnant native grasslands seldom found elsewhere. There is an array of parks and reserves that support rare and diverse flora and fauna species as well as providing highly valued recreation and tourism areas.

The region’s water storage and waterway system, supplemented with water from the desalination plant, provides certainty of potable supply for 75 per cent of Victoria’s population though challenges remain in balancing the supply with the environmental, recreational and Indigenous cultural needs of rivers and streams.

And where the catchments meet the sea are found the jewels in the crown – Port Phillip Bay and Western Port – each with unique and wondrous ecological, economic and community values.

While the region’s natural resources appear to be in generally good condition, you wonder about their sustainability and what impacts the collective lifestyle and management practices are having on the long-term future of the region. Particular attention and action is needed to address established and emerging problems including:

- Increasing urbanisation and the need to protect natural resources and environmental infrastructure from incompatible land uses

- Climate change and its various impacts such as the availability of water to support agricultural production

- The harmful impacts of pests on native plants and animals

- Improving the coordination amongst the many organisations and communities of this region to foster alignment, enhance collaboration and make best use of available resources

- Increasing the collective funding applied to natural resource management in this region

- Managing the inevitable trade offs between economic development in this region and the local environmental health and resilience.

You conclude that, while the region is hospitable, scenic and very productive with many natural resources, important decisions need to be made and actions undertaken in order to pass on the region to future generations in as good or better condition than we have it now.