Values of our rivers, creeks and streams

The Port Phillip & Western Port region holds more than 25,000 kilometres of rivers and creeks. Collectively they gather water from the landscape which flows into Port Phillip Bay and Western Port.

The waterways are very significant for the Traditional Owners of this area. Cultural stories and physical evidence of thousands of years of Aboriginal peoples’ caring for Country are connected to the water and waterways, and Traditional Ecological Knowledge remains important in waterway management today.

The health of the waterways, and the vegetation and wildlife they support, is vital to the region’s environmental, social and economic wellbeing. They provide habitat for plants and animals, and are critically important in sustaining much of our region’s native biodiversity. They also contribute to sustaining critical ecosystem services including nutrient-cycling and carbon sequestration.

Waterways are important for recreation and wellbeing. They are places to escape from busy urban landscapes, to exercise and connect with nature. Waterways and streamside facilities are the most visited part of our region’s National, State and Regional Parks. Around 90 million visits are made to our region’s waterway each year. They are a major contribution to Melbourne being one of the world’s most liveable cities.

Economically, waterways provide benefits through the provision of drinking water for Melbourne and surrounding towns, water for diverse and significant agricultural industries, and supporting travel, tourism, and marine-based activities.

Policy and planning

The Victorian Government’s Water for Victoria policy and the Victorian Waterway Management Strategy provide the state-wide policy framework for water and waterway management.

In the Port Phillip & Western Port region, Melbourne Water is the designated waterway management authority and ‘caretaker of river health’. Melbourne Water has led the development of the Healthy Waterways Strategy 2018-28 which outlines this region’s contribution to meeting the state-wide aims and establishes the vision for the health of rivers, estuaries and wetlands in this region. The strategy articulates a long-term vision and targets for enhanced ‘key waterways values’ (fish, frogs, platypus, birds, macroinvertebrates, vegetation, community connection, recreation and amenity) and sets 10-year objectives as steps to achieve the vision.

Planning and investment for water infrastructure and use is important to underpin the future health of waterways in this region. A Central and Gippsland Region Sustainable Water Strategy has been prepared in response to new population and climate change projections, and focuses on water conservation and efficient use, greater use of recycled water and stormwater, better water-sharing arrangements and improving how water entitlements and trade can be used to better manage risks. Opportunities for the use of recycled water and stormwater are also being explored as part of the Integrated Water Management planning for each of the Westernport, Dandenong, Yarra, Maribyrnong and Werribee catchments, which can lead to improved environmental allocations for river flows and health in the future.

The health of many waterways has been profoundly impacted by the vast volumes of water taken for human uses. The Victorian Environmental Water Holder (VEWH) was established in 2011 to help solve this problem. The VEWH is the legal owner of water allocated to the environment and stored in dams alongside the water allocated to cities, farms and industry. In this region, the VEWH works with Melbourne Water to manage the environmental water it stores in Melbourne Water’s dams. This water is used in carefully managed and timed releases to mimic natural floods, create seasonal flows to trigger fish breeding and to maintain in-stream water quality.

Stream Flow Management Plans (SFMPs) are used in un-dammed catchments where the volume of diversions is known to stress the waterway’s capacity in dry seasons to provide for the environment and water users. Melbourne Water maintains SFMPs for seven sub-catchments in the region: Woori Yallock, Hoddles, Olinda, Stringybark, Steels, Pauls and Dixons Creeks, the Plenty River and the Little & Don Rivers. Southern Rural Water maintains Local Management Rules to protect dry-season flows on Main Creek and its tributaries, Splitters Creek and Rockies Creek in part of the Werribee catchment.

The Environment Protection Authority has a responsibility to protect the uses and values of Victoria’s environment by employing a range of measures consistent with its responsibilities under the new Environment Protection Act 2017 which commenced on 1 July 2021. The Act creates duties for all Victorians to protect our environment and human health from the impacts of pollution and waste. The EPA also performs several activities relevant to waterways including monitoring water quality and regulating discharges to waterways a.

Parks Victoria, councils, farmers, community groups, businesses and individual landowners also manage much of the land through which rivers and creeks flow, and make very important contributions to the health and resilience of waterways and wetlands.

The Victorian Fisheries Authority has in place the Freshwater Fisheries Management Plan that promotes a collaborative approach in the management of our fisheries.

Water and waterway management is also part of a broader aim to ensure all natural resources are managed in a coordinated and integrated way. Outlining this approach, the Victorian Government’s Our Catchments Our Communities: Building on the Legacy for Better Stewardship statement particularly encourages ‘catchment stewardship’ – achieving public benefit (adding environmental, economic, cultural and social value) and going beyond basic duty of care to leave our natural resources in better condition than their current state.

Traditional Owners are the voice of their Country

In all policy and planning processes, the knowledge held by Traditional Owners and Aboriginal Victorians is being increasingly valued, and the influence and involvement of Traditional Owners in planning and management is increasing (see target 13.1). There is recognition that the waterways and lands are interconnected ‘living entities’ and that the Traditional Owners are the ‘voice of the living entities’ on their Country.

Examples of policy and planning processes that are embedding this approach include:

- In 2017, the Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act was put in place, enshrining in law the protection of the Yarra, acknowledging the significance of the river to the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung people and highlighting their ongoing role in its management. Then, in 2021, the Yarra Strategic Plan was finalised to protect and enhance the Yarra River and its land as one living and integrated natural entity.

- In 2018, the Waterways of the West initiative was established as a community-led approach to ensure iconic waterways in Melbourne’s West are protected for generations to come. Traditional Owners were central in this initiative. It led to the Waterways of the West Action Plan outlining priorities for future management.

Condition of this region’s waterways

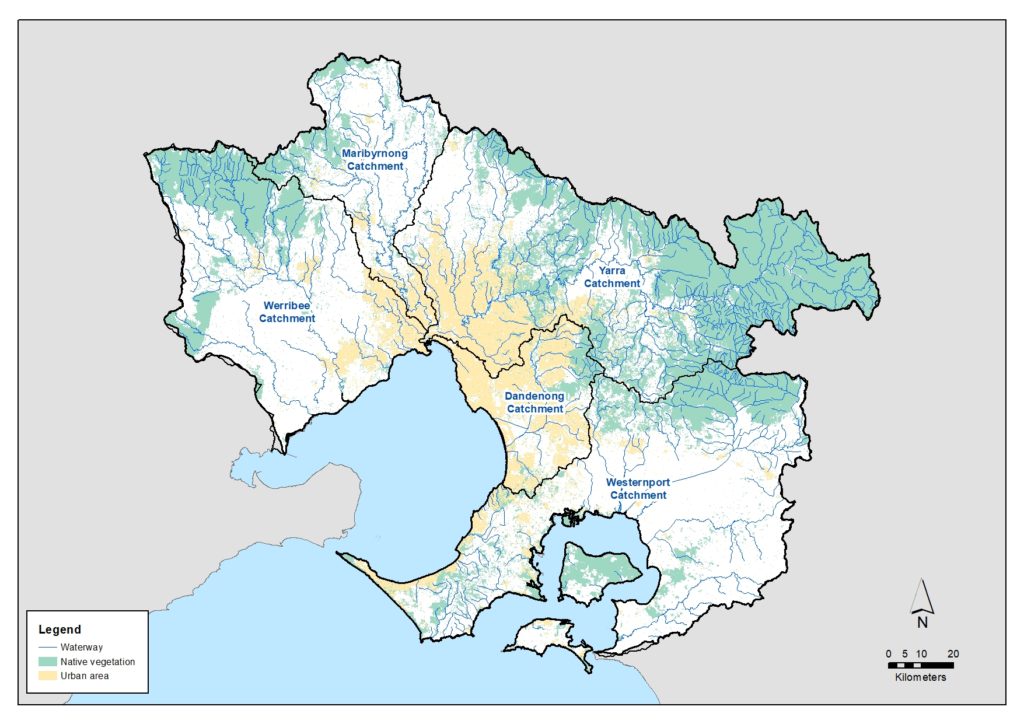

The condition of waterways across the region is outlined in detail in the Healthy Waterways Strategy, describing each of the five major catchments and their particular physical, environmental and socio-economic characteristics and conditions.

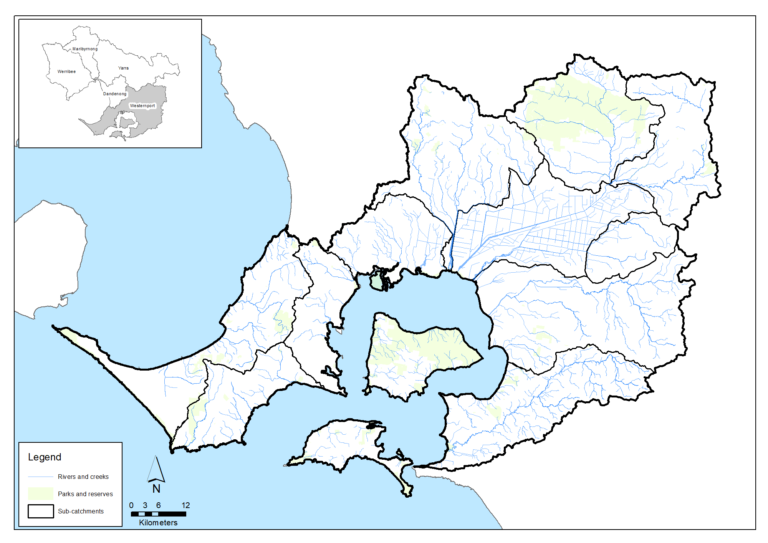

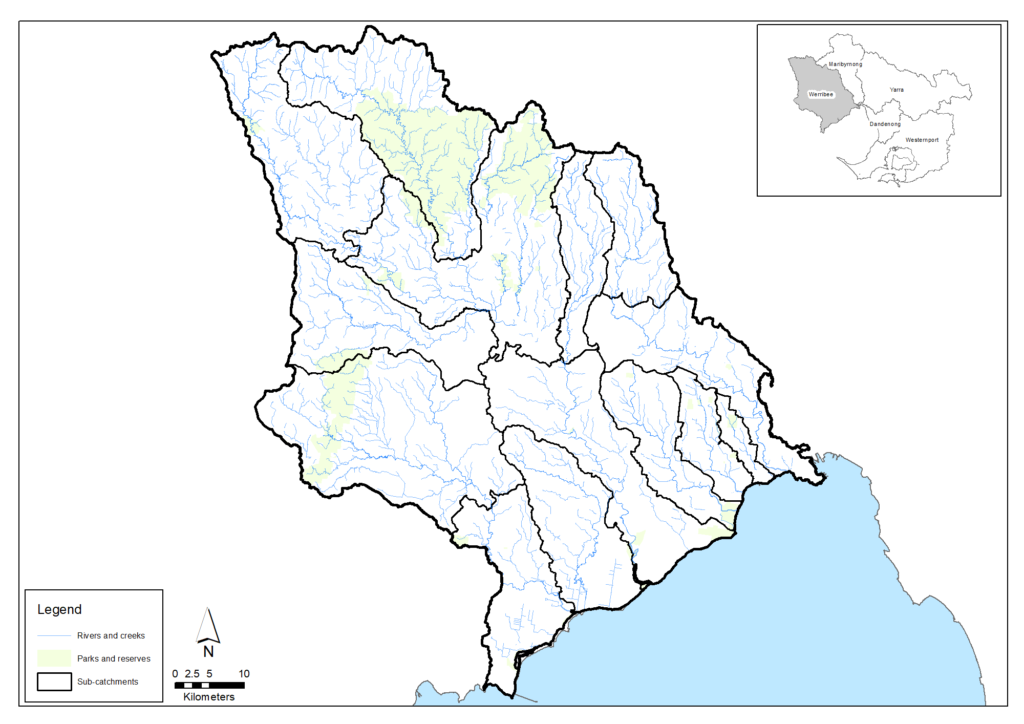

Westernport catchment

The Westernport catchment, including the Mornington Peninsula, occupies about 3,755 square kilometres and includes all the waterways within the catchment for Western Port together with those on Phillip and French Islands and on the Mornington Peninsula (including some that drain to Port Phillip Bay and Bass Strait).

The landscape includes hilly regions near the Bunyip State Park and Strzelecki Ranges, the flat, undulating terrain of the former Koo Wee Rup Swamp and the marine environment of Western Port and its islands.

There have been 249 species of bird recorded, of which 131 species are expected in riparian habitats. The Westernport catchment has important bird habitats including Ramsar-listed Western Port with its extensive network of mangroves, saltmarshes and mudflats.

Threatened species include Australasian Bittern, Hooded Plover, Eastern Great Egret and White-bellied Sea-eagle, and important migratory species such as Eastern Curlew, Red-necked Stint and Curlew Sandpiper.

There are 18 native freshwater fish species and eight exotic fish species recorded in the waterways of the catchment; nationally-significant species include Dwarf Galaxias, Australian Grayling and Australian Mudfish. Frog species include threatened species such as the Growling Grass Frog and the Southern Toadlet.

Vegetation value varies, with much of the higher value areas being in the forested upper catchments, along the coast of Western Port and in the large regional parks.

Assessment of waterway values and conditions in the Westernport catchment at 2018 (from the Healthy Waterways Strategy)

| Waterway values | 2018 state | 2018 trajectory | 2068 target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birds | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Fish | Low | High | High |

| Frogs | High | Moderate | High |

| Macroinvertebrates | Moderate | Low | High |

| Platypus | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Vegetation | Low | Very low | Moderate |

| Amenity | High | Moderate | Very high |

| Community connection | High | Moderate | High |

| Recreation | High | High | High |

| Waterway conditions | 2018 state | 2018 trajectory | 2068 target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stormwater | High | Moderate | High |

| Physical form | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Water for the environment | High | Moderate | High |

| Vegetation quality | Low | Very low | Moderate |

| Vegetation extent | Low | Low | High |

| Instream connectivity | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Water quality - environment | Low | Very low | Low |

| Access | Very low | Very low | Low |

| Litter | High | Moderate | Very high |

| Water quality - recreational | High | Moderate | High |

| Participation | Moderate | Low | Very high |

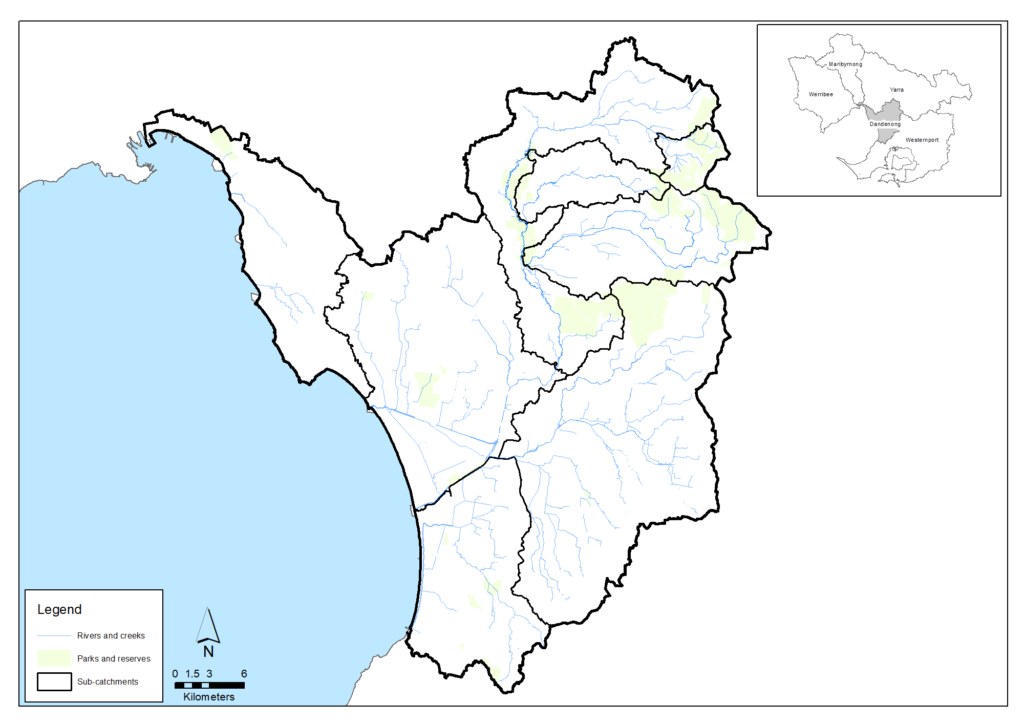

Dandenong catchment

The Dandenong catchment, which covers an area of about 870 square kilometres, consists of forested areas, farmland, reclaimed swampland and urban areas. Urban areas cover about 60 per cent of the catchment, 30 per cent is used for agriculture and about 10 per cent retains its natural vegetation.

Modifications to rivers and creeks for flood protection (such as piping, concrete lining and channel straightening) have been extensive across the catchment. Most notably, the Carrum Carrum Swamp was drained in the late 1800s with the construction of Patterson River. This swamp previously covered about 45 square kilometres. However, the catchment has retained some natural features such as the Ramsar listed Edithvale-Seaford Wetlands (listed as a Ramsar site in 2001, and home to large concentrations of waterbirds including migratory shorebirds), The Pines Flora and Fauna Reserve, the Dandenong Ranges and parts of the middle Dandenong Creek. Closer to the city, waterways such as Elster Creek and Albert Park Lake provide critical habitat for flora and fauna within the constraints of the urban environment.

There are 295 bird species recorded, of which 126 species are riparian specialists. Native fish species and populations have been significantly impacted by the extent of barriers to fish movement throughout the catchment that prevent some species from reaching other parts of the catchment. Frogs across much of the catchment have also been impacted by spreading urbanisation, land use intensification, introduced predators, and deteriorating water quality. However, recorded species include the threatened growling grass frog and the southern toadlet.

Vegetation value varies greatly with much of the higher value areas being in the forested upper catchment and in the large regional parks and wetlands along the Dandenong Creek.

Assessment of waterway values and conditions in the Dandenong catchment at 2018 (from the Healthy Waterways Strategy)

| Waterway values | 2018 state | 2018 trajectory | 2068 target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birds | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Fish | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Frogs | Low | Moderate | Moderate |

| Macroinvertebrates | Very low | Very low | Low |

| Platypus | Very low | Very low | Very low |

| Vegetation | Low | Very low | Low |

| Amenity | High | High | Very high |

| Community connection | High | High | Very high |

| Recreation | High | High | Very high |

| Waterway conditions | 2018 state | 2018 trajectory | 2068 target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stormwater | Very low | Very low | Low |

| Physical form | High | Moderate | High |

| Water for the environment | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Vegetation quality | Low | Very low | Moderate |

| Vegetation extent | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Instream connectivity | Low | Low | High |

| Water quality - environment | Very low | Very low | Low |

| Access | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Litter | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Water quality - recreational | Moderate | Low | High |

| Participation | Low | Very low | High |

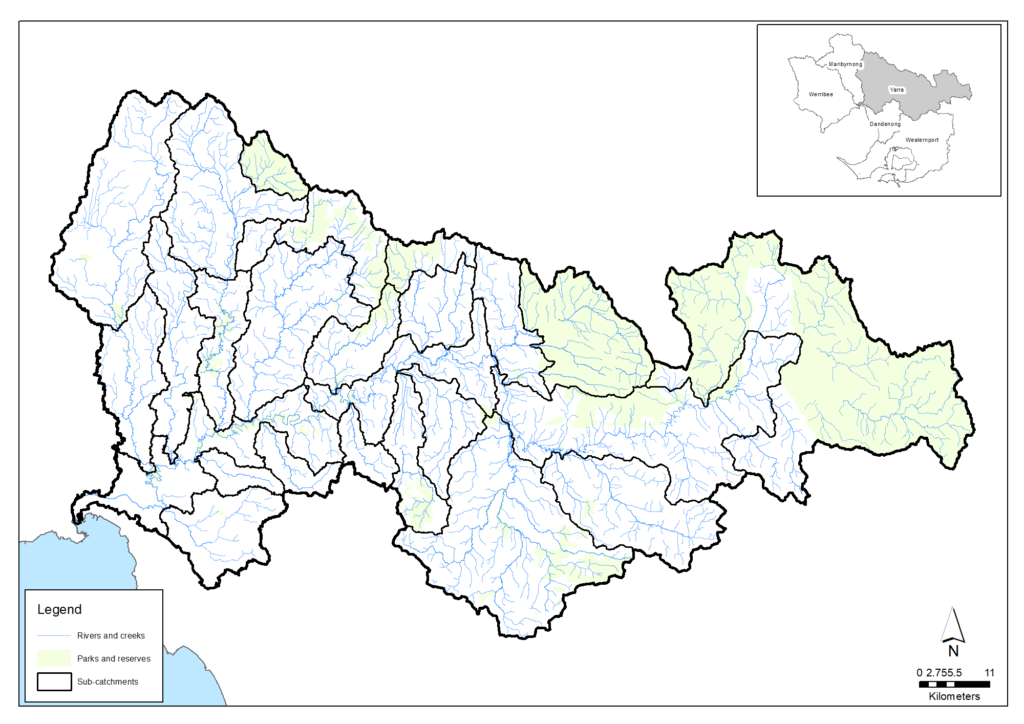

Yarra catchment

The Yarra catchment covers an area of 4,046 square kilometres. Around 55 per cent of the area retains its natural vegetation, 30 per cent is used for agriculture and 15 per cent is urban.

The catchment includes the Yarra (Birrarung) River, which is the largest river in the region. It rises in the Great Dividing Range to the east of Warburton and flows 245 kilometres until entering Port Phillip at Newport. There are over 21,000 wetlands in the catchment, including approximately 16,000 constructed wetlands and nearly 5,100 natural wetlands that support significant environmental and social values.

More than one third of Victoria’s native plant and animal species can be found in the Yarra catchment. Bird species listed as nationally-threatened include the Swift Parrot, Australasian Bittern and Helmeted Honeyeater. There are 16 native fish species, including the nationally-listed Dwarf Galaxis, Macquarie Perch (introduced), Australian Mudfish and Australian Grayling. Frog species include threatened species such as the Growling Grass Frog and the Brown Toadlet.

The condition of native vegetation is highly variable – the upper headwaters contain areas of very high value intact native vegetation protected within the Yarra Ranges National Park, but is degraded further from the headwaters as a result of agricultural activities and increasing urbanisation.

Assessment of waterway values and conditions in the Yarra catchment at 2018 (from the Healthy Waterways Strategy)

| Waterway values | 2018 state | 2018 trajectory | 2068 target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birds | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Fish | Low | Moderate | High |

| Frogs | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Macroinvertebrates | High | High | Very high |

| Platypus | High | Moderate | High |

| Vegetation | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Amenity | High | High | Very high |

| Community connection | High | Moderate | High |

| Recreation | High | High | Very high |

| Waterway conditions | 2018 state | 2018 trajectory | 2068 target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stormwater | Moderate | Low | High |

| Physical form | High | Moderate | High |

| Water for the environment | High | Moderate | High |

| Vegetation quality | Moderate | Low | High |

| Vegetation extent | High | High | High |

| Instream connectivity | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Water quality - environment | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Access | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Litter | High | Moderate | High |

| Water quality - recreational | High | High | High |

| Participation | Moderate | Low | Very high |

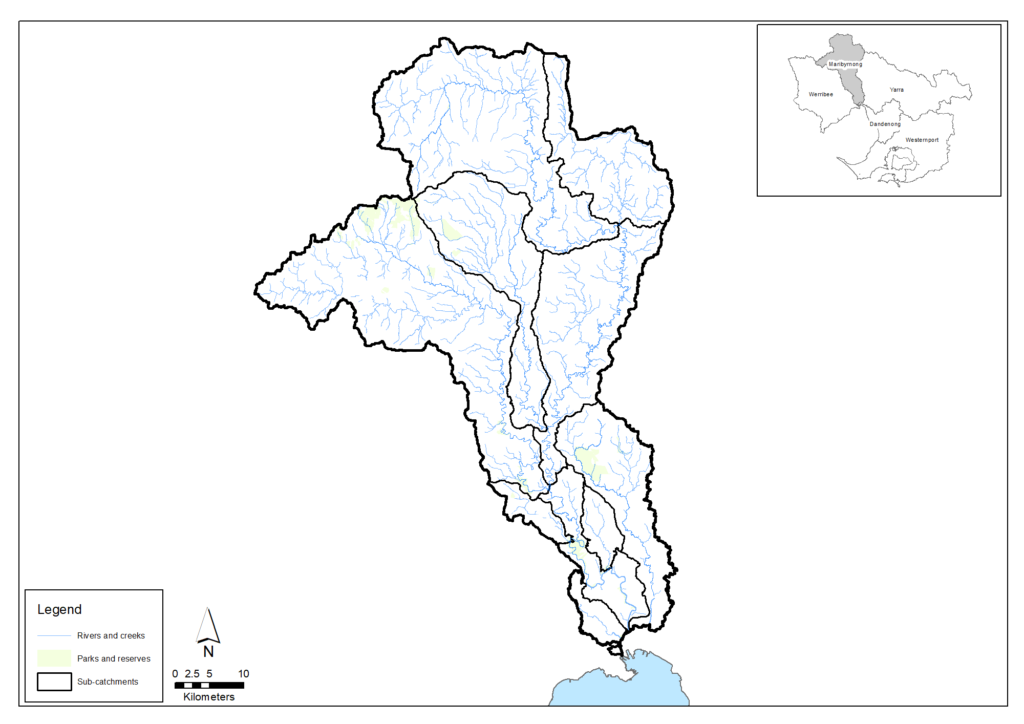

Maribyrnong catchment

The Maribyrnong catchment region covers an area of around 1,408 square kilometres, comprising approximately 10 per cent natural vegetation, 80 per cent agriculture and 10 per cent urban.

The catchment includes the 41-kilometre-long Maribyrnong River – the second major river in the region – which begins on the southern slopes of the Great Dividing Range, in the Cobaw Ranges. It includes a number of important waterways and wetlands, including Stony, Moonee Ponds and Deep Creeks and the Jacana, Pipemakers Park and Queens Park wetlands.

Over 350 bird species are recorded of which 95 species are riparian specialists. There are a number of threatened freshwater species including the Australian Grayling, Yarra Pygmy Perch and Australian Mudfish, and threatened frog species include the Growling Grass Frog, Brown Toadlet and Southern Toadlet.

Much of the higher vegetation and macroinvertebrate value areas are in the forested upper catchment with degradation increasing towards the lower reaches.

Assessment of waterway values and conditions in the Maribyrnong catchment at 2018 (from the Healthy Waterways Strategy)

| Waterway values | 2018 state | 2018 trajectory | 2068 target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birds | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Fish | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Frogs | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Macroinvertebrates | Moderate | Low | High |

| Platypus | Moderate | Very low | Moderate |

| Vegetation | Low | Very low | Moderate |

| Amenity | High | Moderate | High |

| Community connection | High | Moderate | Very high |

| Recreation | High | Moderate | Very high |

| Waterway conditions | 2018 state | 2018 trajectory | 2068 target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stormwater | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Physical form | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Water for the environment | Moderate | Low | High |

| Vegetation quality | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Vegetation extent | Low | Low | High |

| Instream connectivity | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Water quality - environment | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Access | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Litter | High | Moderate | High |

| Water quality - recreational | High | Moderate | High |

| Participation | Moderate | Low | Very high |

Werribee catchment

The Werribee catchment region incorporates rivers and creeks including Little River, Werribee River, Lerderderg River, Toolern Creek, Skeleton Creek and Kororoit Creek, which all drain into the northwest area of Port Phillip Bay. The catchment occupies an area of 2,695 square kilometres, comprising around 20 per cent natural vegetation, 65 per cent agriculture and 10 per cent urban.

There are 134 expected riparian bird species and recent records of nationally-significant fish including the Australian Grayling in the lower Werribee River. Frog species include the threatened Growling Grass Frog, Brown Toadlet and the Southern Toadlet; although neither of the two toadlet species have been recorded in the catchment since the Millennium Drought.

The health of the catchment’s waterways is strongly linked to land use, with the upper reaches in a more natural condition than those in the rural and urban areas. Despite significant impacts from agriculture and urban development across the catchment, waterways continue to support multiple and varied uses and values including water supply, flood mitigation and significant plant and animal species.

Assessment of waterway values and conditions in the Werribee catchment at 2018 (from the Healthy Waterways Strategy)

| Waterway values | 2018 state | 2018 trajectory | 2068 target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birds | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Fish | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Frogs | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Macroinvertebrates | Moderate | Moderate | Very high |

| Platypus | Low | Very low | Low |

| Vegetation | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Amenity | High | Moderate | High |

| Community connection | High | Moderate | Very high |

| Recreation | High | High | High |

| Waterway conditions | 2018 state | 2018 trajectory | 2068 target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stormwater | High | High | High |

| Physical form | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Water for the environment | High | Moderate | High |

| Vegetation quality | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Vegetation extent | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Instream connectivity | Low | Low | High |

| Water quality - environment | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Access | Very low | Very low | Low |

| Litter | High | Moderate | High |

| Water quality - recreational | High | High | High |

| Participation | Moderate | Moderate | Very high |

Major challenges and drivers of change

Many waterways experience constant pressure from people, urban expansion, poor land management and wider environmental change. The major challenges for waterway health in the Port Phillip and Western Port region are listed below.

Climate change

The world is experiencing notable warming of climate and our region is becoming hotter and drier and experiencing more extreme weather (hotter days and more intense storms). Climate change is not new but the rate of change is rapid and, with limited time to adjust, waterway systems are likely to be highly impacted.

The Port Phillip and Western Port region is expecting a median increase in average daily air temperature of between 1.2 and 2.3°C by the middle of this century. At the same time, the region is predicted to experience a median decrease in average annual runoff from the catchments of between 11 and 20 per cent from current levels. We can expect higher maximum temperatures in summer, which may exacerbate urban heat impacts on communities and result in a shift of plant species and generally drier vegetation in the catchments. This in turn may result in an increased risk of bushfire. There is expected to be more unpredictable weather patterns, with higher intensity storms resulting in times of high peak flows in the region’s drains and waterways.

For waterways, intense stormwater events are known to result in poorer water quality, increased sediment and nutrient loads, reduced dissolved oxygen, rapid alteration of habitats, and reduced amenity and access for communities. Over the longer term, warming and drying trends are likely to affect the plants and animals that can survive along waterways and around wetlands. Sea level rise and storm surges may also affect soil and water salinity, water levels and the physical form of coastal areas and may in turn influence coastal plant and animals communities.

Projected climate change effects on waterways and wetlands include:

- Stream flows could be reduced by up to 35% by 2050

- While stream flows decline, water supply demand may grow and larger parts of available stream flows could be diverted

- More frequent bushfires may reduce water quality and catchment inflows

- Increasing water temperatures and reduced flows may damage waterways and wetlands as natural environments

- More intense rainfall and ‘flash’ floods may do economic, social and environmental damage to waterways.

Urbanisation

The Port Phillip and Western Port region supports a population of more than five million people with a predicted increase to eight million or more people by 2050. The impervious footprint across the region is currently around 1,100 square kilometres but over 39,000 dwellings are added each year that will generate an increase to 1,750 square kilometres over the next 50 years.

As Melbourne experiences continued population growth and urbanisation, it will be a challenge to maintain and improve waterway health so that waterways can continue to support prosperity, liveability and wellbeing.

A major impact is that, as vegetated surfaces are replaced with hard, impervious surfaces (such as roofs, roads and paved areas) that drain directly into waterways via stormwater systems, infiltration to the soil and groundwater system is reduced. This affects the waterway system in two ways: rapid runoff in wet conditions, and lack of soil moisture during dry conditions. Increased and rapid runoff to waterways during, and shortly after, rain events leads to scouring of aquatic habitats, and a heavier load of urban pollutants, including oils, dirt, nutrients, heavy metals, pesticides and litter. Changing flow regimes and water quality affect the habitats and health of platypus, fish, invertebrates and other aquatic animals, and naturally-saline wetlands and waterways in the lower parts of catchments. These changes have major impacts on instream and riparian flora and fauna.

In recognition of these issues and the need to manage the impacts, various policy and planning mechanisms are being utilised by the Victorian Government, municipal councils and others. For example, in 2009 a number of Victorian councils coordinated their efforts to introduce a consistent Environmentally Sustainable Development (ESD) policy into their planning schemes. Six councils – Banyule, Moreland, Port Phillip, Stonnington, Whitehorse and Yarra – successfully had an ESD Local Planning Policy gazetted in November 2015. Other councils have since pursued a similar approach with numerous policies now gazetted. Positive outcomes are being generated with new permit applications demonstrating significantly improved sustainability outcomes in daylight and natural ventilation, stormwater management and energy efficiency.

Enhancing urban waterway amenity

Waterway amenity is the physical and visual qualities of a waterway and its surrounds that influence people’s experience of naturalness, escape, and safety. Amenity includes the character of the landscape and the vistas and views from and to the rivers, the environmental condition of waterways as well as the many benefits that parklands and open spaces provide along them. The ability to access and safely enjoy spaces is a key aspect of a place’s amenity. The cultural values attached to the rivers and their recreational uses and facilities are also related to waterway amenity.

Over thousands of generations and as the original custodians of land and waters, Traditional Owners have considered waterways and their corridors as interconnected living systems and places of sacred sites, resources, values and stories that need to be cared for in a whole unfragmented way – from source to bay.

Today, the waterways of the Port Phillip and Western Port region, including their corridors, are well loved and visited places that contribute to human health and well-being.

In a large urban environment that aims to create ’20 minute neighbourhoods’ with daily services and open space located within an 800 metre walk from homes, waterways continue to offer a place where communities can recreate, exercise, commute, connect (with nature and each other) and find respite, restoration, beauty and spiritual fulfilment.

The sense of well-being associated with waterways depends on the physical and visual qualities of waterways and their surrounds. These include the possibility to see water and hear the sounds of nature such as bird calls, water and wind, the surrounding vegetation and absence of litter, the ability to access the waterway, the provision of facilities and the quality and extent of open space. Urban intrusion through sight, sound and smell play a key role in diminishing amenity perceptions of urban rivers.

If not protected and proactively invested in, these physical and visual qualities can be irreversibly compromised and opportunities for the many Melbournians who do not have suitable access to open space and nature missed.

In the past few years, waterway management in the Port Phillip and Western Port region has evolved to better recognise the multiple values of waterways and the many agencies and community groups who play a role in enhancing the cultural, environmental, social and economic values of waterways.

In a growing city, aligning community and agency efforts is critical to protect and enhance waterway amenity. It requires:

- common visions and targets, as outlined in this Regional Catchment Strategy and the Healthy Waterways Strategy

- an understanding of how each community and agency partner can contribute

- mutually beneficial ways of planning, working and learning together, including opportunities to better align projects, service provision and investment, advocate and resolve issues

- supportive planning policy and framework

- the ability to consider the full length of waterways, their corridors and the biolinks they connect to, beyond single jurisdictional boundaries.

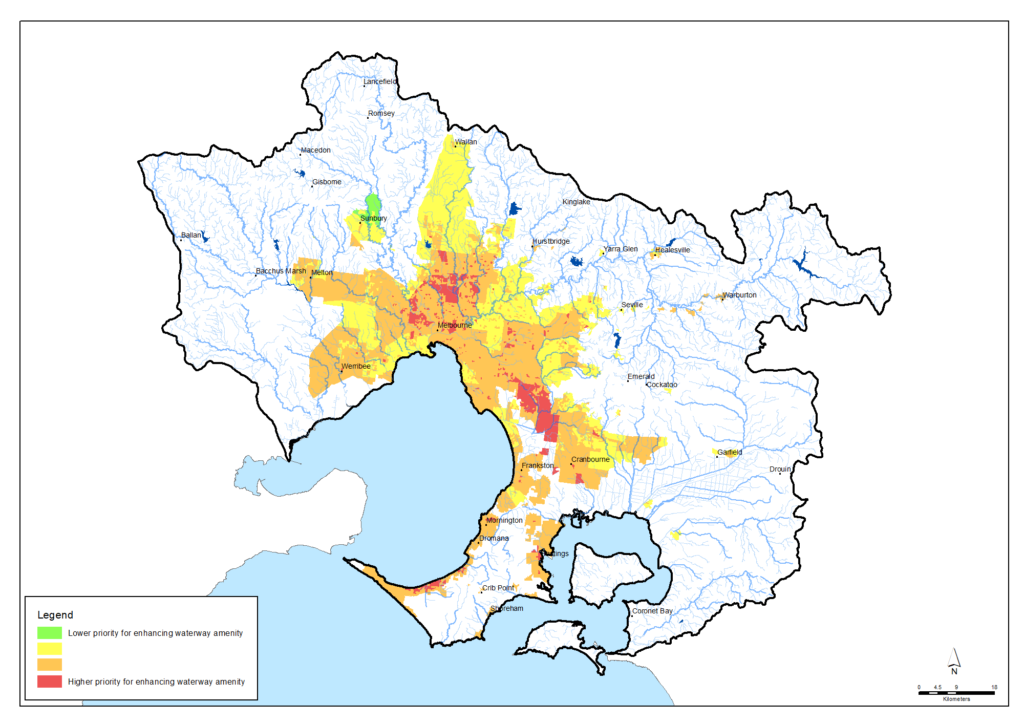

The following map is a preliminary assessment that shows where enhanced access to green spaces and urban waterway amenity would generate the greatest community health and well-being benefits. The assessment considers the following factors: heat vulnerability, socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA), mental health data, physical health data, household access to public open space within 400 metres, area of public open space per person (hectares), current population and future population forecasts (at 2036). Further detail about this data can be obtained by emailing liveability@melbournewater.com.au. This information can support organisations and land managers make planning decisions related to protecting, optimising and growing Melbourne’s open space and urban waterway amenity network. Key urban waterways with a high need for enhanced amenity and access to nature and green spaces experiences include:

- Western catchments – Werribee River (near Werribee township), Maribyrnong River, Moonee Ponds Creek, Stony Creek and Steele Creek (Airport West)

- North eastern catchments – Merri Creek (middle catchment around Coburg and Fawkner), Edgars Creek (Reservoir), Darebin Creek (Preston) and Gardiners Creek (around Burwood).

- South east catchments – Dandenong Creek (around Dandenong and Springvale) and Mile/Yarraman Creeks (Noble Park).

The methods and information to assess urban waterway amenity priorities, and the resultant mapping, are expected to improve in coming years, led by Melbourne Water and the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action.

Pollution

Pollutants such as chemicals, pathogens, nutrients, excess sediment, heavy metals and other toxicants threaten environmental values of waterways. They can enter waterways through; inappropriate use of agricultural or domestic herbicides, pesticides and fungicides; sediment from erosion and soil disturbance; leaching of contaminants through soil and groundwater; illegal dumping into stormwater drains and waterways; licenced discharges from treated effluent; untreated dairy effluent; sewer spills and leaks; illegal sewerage connections to the stormwater system; septic tanks; and industrial discharges.

Pollution results in physical, chemical and biological impacts on the receiving environment. Impacts can be directly on the chemical balance of the waterway, or on amenity or ecosystems, and may cause fish kills, blue-green algal blooms, and health and odour issues that make it unsafe for human contact.

Changes to natural water flows

River flows are impacted by surface water and groundwater harvesting for urban drinking supply and for domestic, stock and agricultural uses. The impacts of these extractions are acutely noticed during low flow periods, although all components of the flow or inundation regime of waterways are significant for their ecology. (For example, they provide triggers for breeding or migration of fish and they affect the connectivity of floodplain habitats to rivers.)

Very low flows can lead to a reduction in habitat for values including platypus, frogs and fish, and very high flows can destroy important in-stream habitat and features such as pools and small rapids. Changes to natural flows combined with other threats can also lead to loss of species entirely from some systems.

Ongoing extraction across the landscape has potentially long-term effects on water flows and waterway health, particularly if extraction rates are not carefully managed.

Small farm dams can also collectively reduce stream flows. The large number of dams on hobby farms and rural-residential properties in some rural catchments may capture significant amounts of water before it reaches local creeks. However, permits are not required to build or use water from off-stream dams for domestic, stock water or ornamental purposes

Vegetation clearing

Vegetation removal for development and grazing by livestock can significantly impact the physical form and ecological health of waterways. These stressors decrease bed and bank stability, reduce the quality of instream and streamside habitat, alter levels of organic matter in the waterway (vegetation adds organic matter beneficial to stream biota, and livestock add faeces), and alter temperature and light regimes. These combined impacts not only affect aquatic biodiversity, but also the sense of naturalness that contributes to amenity. Removal of habitat such as vegetation along waterways also has a significant impact on the connectivity of plants and animals across the landscape.

Pest plants and animals

Pest plants and animals diminish the social, environmental and water resource values of waterways. Pest plants and animals are a region-wide problem demanding coordinated investment and action by public agencies, community and landholders.

Exotic weeds, including invasive willows and poplars, impact the healthy functioning of waterways. They alter stream channel forms and water flows, disrupt aquatic food chains, degrade native animal habitats, outcompete native vegetation and alter the chemical compositions of water and soil.

Foxes, feral dogs and feral cats prey on or competing with platypus, birds, reptiles and mammals. Grazing and browsing animals such as rabbits and deer damage vegetation communities and groundcover. Wild deer and pigs can pollute drinking water supplies with human-infectious pathogens.

The region’s estuaries face growing risks from aquatic and marine pests. Climate and water temperatures changes, increasing stormwater and nutrient pollution and growing recreational boat traffic increase the likelihood of new aquatic and marine pest introductions. Exotic pests compete with native species and fish stocks, degrade habitats and potentially disrupt natural nitrogen cycling processes.

Vision and targets for the future

Vision

The Healthy Waterways Strategy outlines the following 50-year vision:

Healthy and valued waterways are integrated with the broader landscape, and enhance life and liveability. Waterways connect diverse and thriving communities of plants and animals; provide amenity to urban and rural areas, and engage communities with their environment; and are managed sustainably to enhance environmental, economic, social and cultural values.

The Healthy Waterways Strategy also provides catchment-scale visions, as summarised below.

Targets

Following is a small selection of the targets in the Healthy Waterways Strategy to help achieve the visions for waterways across the region. More detail on the ratings of waterways are available in the Healthy Waterways Strategy. Progress towards these targets will be primarily monitored through the ongoing Healthy Waterways Strategy monitoring and reporting program led by the Melbourne Water.

Target 2.1 – Fish in waterways

Target 2.2 – Waterway amenity

Target 2.3 – Vegetation extent along waterways

Target 2.4 – Vegetation quality along waterways

An additional target regarding environmental water supply is included in the Water supply and use section of this Regional Catchment Strategy.

Partner organisations

The following organisations formally support the pursuit of the visions and targets for waterways. They have agreed to provide leadership and support to help achieve optimum results with their available resources, in ways such as:

- Fostering partnerships and sharing knowledge, experiences and information with other organisations and the community

- Seeking and securing resources for the area and undertaking work that will contribute to achieving the visions and targets

- Assisting with monitoring and reporting on the condition of the area.

Victorian Government

- Melbourne Water

- Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA)

- Parks Victoria

- Victorian Planning Authority

- Environment Protection Authority Victoria (EPA)

- Sustainability Victoria

- Victorian Fisheries Authority

- Trust for Nature

- Southern Rural Water

- Greater Western Water

- Yarra Valley Water

- South East Water

- South Gippsland Water

- Westernport Water

- Zoos Victoria

Local Government

- Hume City Council

- City of Whittlesea

- Macedon Ranges Shire Council

- Moorabool Shire Council

- City of Greater Geelong

- Monash City Council

- Bayside City Council

- Glen Eira City Council

- Kingston City Council

- Knox City Council

- Maroondah City Council

- Manningham City Council

- City of Casey

- Cardinia Shire Council

- Baw Baw Shire Council

- Bass Coast Shire Council

- Wyndham City

- Hobsons Bay City Council

- Brimbank City Council

- Moonee Valley City Council

- City of Melbourne

- City of Port Phillip

- City of Stonnington

- City of Greater Dandenong

- Whitehorse City Council

- South Gippsland Shire Council

- Eastern Region Pest Animal Network

- Western Alliance for Greenhouse Action

- Northern Alliance for Greenhouse Action

- South East Councils Climate Change Alliance

- Eastern Alliance for Greenhouse Action

Traditional Owners

- Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation

- Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation

Non Government

- The Nature Conservancy

- Conservation Volunteers Australia

- Marine Mammal Foundation

- Dolphin Research Institute

- Birdlife Australia

- The People and Parks Foundation

- Field Naturalists Club of Victoria

- Victorian National Parks Association

- Native Fish Australia (Vic)

- OzFish Unlimited

- Gardens for Wildlife Victoria

- Victoria Walks

- Port Phillip EcoCentre

- Western Port Seagrass Partnership

- Habitat Restoration Fund

Community

- Werribee River Association

- Friends of Lower Kororoit Creek Inc

- Nillumbik Landcare Network

- Federation for Environment and Horticulture in the Macedon Ranges

- NatureWest

- Jacksons Creek EcoNetwork

- Greening of Riddell

- Friends of Daly Nature Reserve

- Friends of Emu Bottom Wetlands Reserve

- Deep Creek Landcare Group

- Riddells Creek Landcare Group

- Newham and District Landcare Group

- Upper Deep Creek Landcare Network

- Little River Community Landcare Inc

- Yarra Ranges Landcare Network

- Northern Yarra Landcare Network

- Nangana Landcare Network

- Johns Hill Landcare Group

- Merri Creek Management Committee

- Darebin Creek Management Committee

- Abbotsford Riverbankers Inc

- Gippsland Threatened Species Action Group

- Yarra Riverkeeper Association

- Mornington Peninsula Landcare Network

- Main Creek Catchment Landcare Group

- Merricks Coolart Catchment Landcare Group

- Sheepwash Creek Catchment Landcare Group

- Manton and Stony Creeks Landcare Group

- Red Hill South Landcare Group

- Cardinia Environment Coalition

- Bass Coast Landcare Network

- Bass Valley Landcare Group

- South Gippsland Landcare Network

- Loch-Nyora Landcare Group

- Mt. Lyall Landcare Group

- Poowong & District Landcare Group

- Triholm Landcare Group

- Phillip Island Landcare Group

- Western Port Catchment Landcare Network

- Westernport Swamp Landcare Group

- Friends of Dandenong Valley Parklands

- Kooyongkoot Alliance

- Friends of Olinda Creek

- Mornington Peninsula Koala Conservation

Add your organisation as a supporter and partner

If your organisation supports these directions and targets for waterways and wishes to be listed as a partner organisation, you can request to be listed as a partner organisation. Adding your organisation to this list will:

- enable your organisation to list one or more priority projects in the Prospectus which will describe how your priority project will pursue the targets of this Regional Catchment Strategy and potentially make your organisation’s project more attractive to investors by using the strategy to highlight its relevance and value

- demonstrate your commitment to a healthy and sustainable environment

- demonstrate the level of community engagement and support for this work.

Priority projects to move forward

Priority projects

There are significant ongoing programs and initiatives undertaken by many organisations in this region that are vital for protecting and enhancing waterways. For example, there are collaborative programs under way including the Healthy Waterways Strategy implementation, Stream Frontage Management Program, Corridors of Green and Enhancing Our Dandenong Creek.

In addition, there are numerous project proposals that, if funded and implemented, can contribute to achieving the visions and targets for waterways. Potential projects include:

- Westmeadows Meander led by the Chain of Ponds Collaboration

- Moonee Ponds Creek Litter Action led by the Chain of Ponds Collaboration

- Upper Arthurs Creek and streamsides proposed by the Strathewen Landcare Group

- Fish habitat in the Maribyrnong River proposed by OzFish Unlimited

- Little River Weir improvement proposed by Little River Community Landcare Inc

- Dunns Creek Rehabilitation led by Dunns Creek Landcare Group

- Woori Yallock Creek Vegetation Improvement proposed Melbourne Water

- Regenerating Gardiners Creek (Kooyongkoot) led by Stonnington City Council

- Deep Creek Biolink proposed by Upper Maribyrnong Catchment Group

- Merri Creek Biolink led by Merri Creek Management Committee

- Merri Creek Community Engagement led by the Merri Creek Management Committee

- Jacksons Creek cultural landscapes proposed by Melbourne Water

- Jacksons and Riddells Creeks Wildlife Corridor proposed by Jacksons Creek EcoNetwork

- Jacksons Creek & Emu Bottom Wetland Rabbit Control proposed by Melbourne Water

- Lower Dandenong Creek Litter Collaboration led by Melbourne Water

- Reimagining Arnolds Creek led by Melbourne Water

- Reimagining your Moonee Ponds Creek led by Melbourne Water

- Patterson River Litter Trap led by Melbourne Water

- Mordialloc Creek Rehabilitation and Wetlands Project led by Melbourne Water.

A list of project proposals and their key details can be viewed on the Prospectus page of this Regional Catchment Strategy.

Propose a new priority project

As part of the ongoing development and refinement of this Regional Catchment Strategy, additional priority projects may be considered for inclusion in the Prospectus.

If your organisation supports the directions and targets for waterways, and has a project proposal it would like highlighted and supported in this Regional Catchment Strategy, please complete and submit a Prospectus Project Proposal.