Western Port

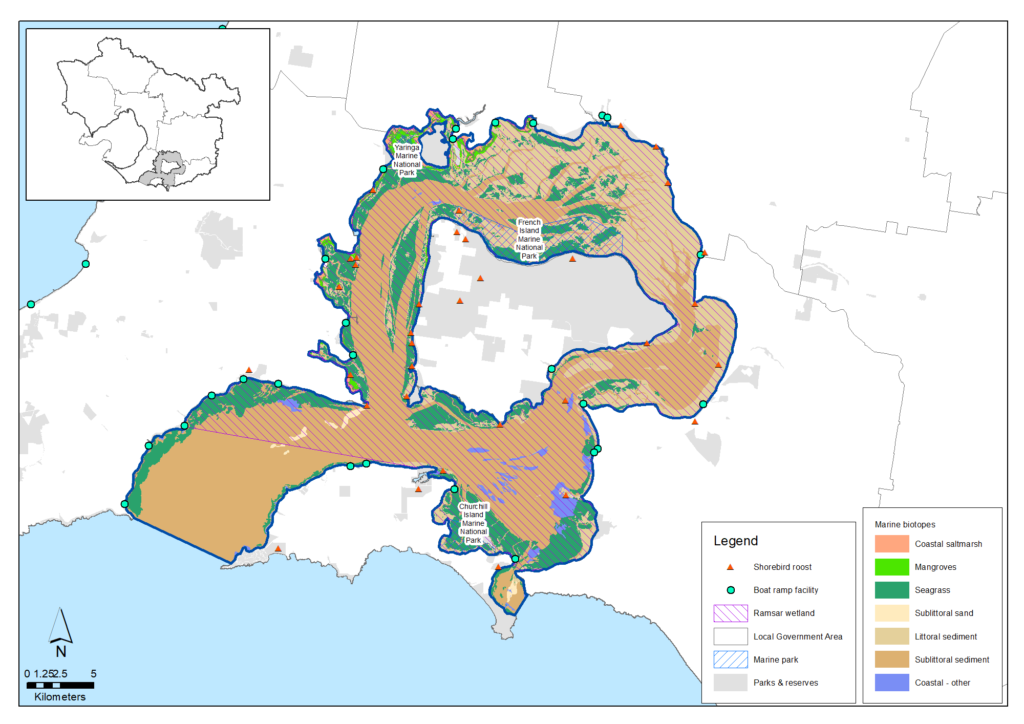

Western Port is a natural wonder on the edge of Australia’s second-largest city. Western Port’s outstanding biodiversity is founded on a mosaic of marine, intertidal, coastal, wetland and island environments.

Western Port is a Ramsar Site – a wetland of international importance. The Ramsar Convention aims to halt and reverse the worldwide loss of wetlands and to conserve those that remain. Wise use and management’ are the convention’s key principles.

Western Port’s shores are fringed by some of the world’s most southerly mangrove forests, vast intertidal mudflats, Victoria’s largest saltmarshes and sandy beaches.

Beneath the water, seagrass meadows grow across Western Port’s northern and western arms around French Island. They provide critical habitat and energy for fish and the invertebrates they live on.

Deep, steep-walled tidal channels allow 2-3 metre tides to sweep through the bay four times each day. At low tide, approximately 40% of Western Port is exposed mud and seagrass. Well-mixed oceanic waters produce clean, coarse sands on the seabed at Western Port’s southern reaches. In the north-eastern parts of the bay the waters become more turbid and the sediments finer. Rocky reefs are not common in Western Port but support rich diversities of invertebrates and seaweeds.

Birdwatchers and scientists have counted 115 species of waterbirds, waders and seabirds. They account for 65% of Victoria’s bird species diversity and over 30 migratory waterbird species listed under international conservation agreements.

Policy and planning

The Marine and Coastal Act (2018) provides an integrated and coordinated approach to planning and managing Victoria’s marine and coastal environment. The Marine and Coastal Policy guides decision makers in the planning, management and sustainable use of Victoria’s marine and coastal environment. The first statewide Marine and Coastal Strategy includes an implementation plan identifying priority actions to be completed over the next five years, and outlines responsibility for delivery and timeframes.

Responsibility for planning and development on Western Port’s coasts and seabed generally lies with the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action, which also oversees the legal accountabilities of several Coastal Committees of Management around Western Port.

The Department also coordinates Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037 – the Victorian Government’s statewide strategy to protect and improve biodiversity.

Western Port’s catchment lands and coasts are generally managed by four local governments – the Mornington Peninsula, Casey, Cardinia and Baw Baw Councils. They have range of policies and plans in place that aim to protect and enhance Western Port’s cultural, social, environmental and economic values, including:

- City of Casey Biodiversity Strategy 2018

- Shire of Cardinia Biodiversity Conservation Strategy 2019-2029

- Bass Coast Shire Natural Environment Strategy 2018-2022

- Mornington Peninsula Biodiversity Conservation Plan 2019

- Mornington Peninsula Shire Interim Green Wedge Management Plan

- Mornington Peninsula Stormwater Management Plan.

Victoria also has a system of Marine Protected Areas. In Western Port there are three marine areas. These are managed by Parks Victoria. Parks Victoria also has responsibilities as the Local Port and Waterway Manager and has a Safety and Environmental Management Plan in place that covers Port Phillip Bay.

The Environment Protection Authority has a responsibility to protect the uses and values of Victoria’s environment by employing a range of measures consistent with its responsibilities under the new Environment Protection Act 2017 which commenced on 1 July 2021. The Act creates duties for all Victorians to protect our environment and human health from the impacts of pollution and waste. Under the Act, the General Environmental Duty (GED) and other more specific duties will focus Victorian business, industry and the community on preventing harm. The EPA also performs several activities relevant to marine environments including monitoring recreational and marine water quality, regulating discharges to waterways and coastal waters, and reporting on the condition of the bays and catchments.

Melbourne Water manages the waterways, wetlands and estuaries that feed into Western Port. The Healthy Waterways Strategy 2018-28 provides vision statements, goals and performance objectives for waterway management in the catchments.

A key document regarding ecological health in and around Western Port is the Western Port Ramsar Site Management Plan. It identifies priority threats to Western Port’s ecological character and sets management strategies, resource condition targets and monitoring arrangements. The current plan expires in 2022.

The Mornington Peninsula and Western Port Biosphere Reserve Foundation also works with its community to create a sustainable future for Western Port – environmentally, socially and economically. The Foundation’s mission statement is ‘Growing connections for sustainability‘.

Traditional Owners are the voice for their Country

For all policy and planning, there is a need for recognition and inclusion of Traditional Owner knowledge and aspirations. The water and land are increasingly being recognised as ‘living and integrated natural entities‘ and the Traditional Owners should be recognised as the ‘voice of these living entities’.

A Country Plan is being prepared by the Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation which will describe the vision and priorities of the Traditional Owners for their area under their responsibilities as a Registered Aboriginal Party, including for Western Port.

The condition of Western Port now

Water quality

Using five parameters to assess marine water quality (clarity, dissolved oxygen, nutrients, salinity and algal concentrations), the EPA Report Card 2018-19 assessed Western Port’s overall water quality as ‘Good’. Higher nutrient levels and lower water clarity resulted in ‘Fair’ and ‘Poor’ ratings for those two parameters respectively. Conditions in Western port have remained relatively steady since 2000 with overall annual water quality assessed as ‘Good’ for nearly all years since then.

Ecological character

Western Port’s environmental social and economic values depend on its ecology – the abundance, health and connectedness of its land and water and biodiversity. The international system for conserving Ramsar sites calls these qualities and processes ‘ecological character’.

The Western Port Ramsar Site Management Plan ranked nine critical components of Western Port’s ecological character for priority management:

- Seagrass

- Fish

- Waterbird abundance and diversity

- Waterbird breeding

- Threatened species (fish and birds)

- Saltmarsh

- Intertidal sand and mud flats

- Rocky reefs

- Mangroves.

Marine Protected Areas

Four Marine Protected Areas help secure Western Port’s wildlife and marine environments:

- Churchill Island Marine National Park (670 hectares)

- French Island Marine National Park (2,800 hectares)

- Yaringa Marine National Park (980 hectares)

- Mushroom Reef Marine Sanctuary near Flinders.

The San Remo Marine Community is listed under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act.

Biodiversity

Seagrass occurs in four species in Western Port, mostly in its northern and western arms. Its extent and condition have proved highly variable over time. Between the mid 1970s and 1984 the seagrass cover in Western Port fell from 25,000 hectares to 7,200 hectares. Sediments smothering the seagrass is thought the most likely cause of the decline. Mapping to 2011 showed localised increases in some areas of Western Port but declines around Yaringa and in Corinella where poor water quality prevented seagrass recovery or continued its decline. By 2013, total cover had increased to over 15,000 hectares; 60% of its status 40 years earlier.

Fish diversity and abundance in Western Port reflect the quality and diversity of its habitats. Western Port is a key breeding area for some species such as elephant fish, school shark (Galeorhinus australis) and Australian anchovy (Engraulis australis), and a nursery area for other species such as King George whiting (Sillaginodes punctatus), yellow-eye mullet (Aldrichetta forsteri) and Australian salmons (Arripis spp.). Western Port is also important for fish species that migrate between fresh, estuarine and marine waters including the Australian grayling, black bream and the short-finned eel.

Bird abundance remains a vital part of Western Port’s value. 115 species have been recorded on Western Port’s coasts and intertidal areas. Western Port provides important foraging and roosting areas for shorebirds and habitat for waterbirds including ducks and swans, large wading birds such as herons, ibis and spoonbills and for gulls and fish-eating birds such as cormorants, pelicans and terns.

Beach-nesting birds, Australian fairy terns and Caspian terns, breed on Rams Island. Australian pied oystercatchers breed on French Island’s sandy beaches and saltmarshes. Many species of waterbird such as ibis, spoonbills and cormorants breed in swamps and wetlands outside the Western Port Ramsar site boundary but may rely on feeding grounds in the Ramsar site during nesting.

Threatened species continue to persist in Western Port. Threatened wetland birds include Eastern curlews, Curlew sandpipers, Fairy terns, Bar-tailed godwits, Lesser sand plovers and Red knots. Recent environmental flow improvements for the Bunyip River appear to have strengthened populations of the threatened Australian Grayling.

The Orange-bellied parrot is in serious decline and to 2015, had not been recorded in the Western Port for over two decades. A single record for an Australian painted snipe from Pyramid Rock in 1979 is insufficient to indicate that the site supports this species. Hooded plovers are recorded as nesting at Silverleaves beach on Phillip Island but the ocean beaches on the southern shore of Phillip Island are much preferred habitat.

Saltmarsh surveys reported in Understanding the Western Port Environment indicated that as much as 85% of its pre-European extent has been preserved in Western Port. About 1,140 hectares remain despite substantial losses around the Hastings foreshore and marina, and industrial development at nearby Long Point and at The Inlets.

Intertidal sand and mudflats cover an area of approximately 27,000 hectares, nearly half of Western Port Ramsar site area of approximately 60,000 hectares. One of the outstanding characteristics of the soft-sediment fauna of Western Port is the diversity of invertebrates including unique ghost shrimp species. Exposed at low tide, the sandbanks and mudflats are vital feeding grounds for shorebirds, including internationally migratory waders. The Western Port Ramsar Site Management Plan defines ‘no loss of intertidal mudflat area’ as a limit of acceptable change. But the plan reported a lack of current information on the extent of intertidal mudflat area.

Rocky Reefs comprises a small area in Western Port, but includes the intertidal and subtidal reefs at San Remo, which support a high diversity of one invertebrate group, opisthobranchs (sea-slugs and seahares), which are listed as a threatened community. Crawfish Rock, although small, is considered especially diverse: 600 species have been documented at this site: 130 algae, 150 sponges, 50 hydroids, 180 bryozoans and 80 ascidians (Shapiro 1975). In addition, the rare hydroid Ralpharia coccinea is found at Crawfish Rock and may be endemic to Western Port.

Mangroves and saltmarsh are vital to Western Port’s character and abundance. Mangrove roots and pneumatophores (aerial roots) provide habitat and food for invertebrates and fish and erosion protection for coasts and intertidal mudflats. A report by Smythe (1842) found much of the shoreline of the bay covered in mangroves except the clay cliffs near Koo Wee Rup and parts of Phillip Island. By the mid-1980s, only 40% of the mid shoreline around the bay supported mangroves. Losses have been caused by harvesting for soap manufacture, land reclamation near Hastings, and mangrove fringes appear more scattered and discontinuous along the western and southern shores of French Island and at Pioneer Bay.

Mangrove recovery is occurring where sediment conditions have become more stable after a century of catchment changes that moved enormous quantities of eroded sediment into Western Port. Community-led work has seen mixed success in replanting mangrove seed and seedlings by hand along Western Port’s northern and eastern coasts.

Recreational and economic values

Western Port is a famous recreational fishery. Catches range from whiting and school shark over seagrass meadows and snapper, Australian salmon, snook and barracouta in open waters.

Boating and sailing are popular recreations. Western Port hosts four yacht clubs, two large marinas and numerous well-equipped launch ramps.

The commercial Port of Hastings services around 75 ships per year and contributes around $67 million annually to the region’s economy.

Western Port’s coast and catchment

Some of Western Port’s coasts and hinterland are partly protected in the French Island National Park (11,000 hectares), the North Western Port Nature Conservation Reserve (2,047 hectares), the Western Port Intertidal Reserve (446 hectares), the Reef Island and Bass River Mouth Nature Conservation Reserve (29 3hectares), the Warrangine and Crib Point Coastal Reserves (195 hectares) and the Phillip Island Nature Parks (approx. 1,500 hectares).

Most of the wider catchment is modified to support rural and green wedge land uses, though there are still some significant environmental values. Approximately 70% of the catchment is considered agricultural land supporting primary industries include dairying, beef production, poultry, horticulture and quarrying. Urban, industrial and tourist areas, and lifestyle and hobby farms make up a smaller proportion and some forested areas remain in the upper catchment, French Island and the Mornington Peninsula.

Challenges we face

The Western Port Ramsar Site Management Plan identified six priority threats for management during 2015-2022: pest plants and animals, climate change, recreation and water pollution from nutrients, sediments and toxicants.

Pest plants and animals

Invasive Cord-grass (Spartina spp.) is a highly invasive weed capable of displacing native plants and saltmarsh, disrupting food webs and occupying coastal and estuarine habitats above and below the high tide mark. Spartina anglica and Spartina × townsendii have invaded the northern shoreline around the Inlets and Bass River and could become more widespread. Spartina control is a high priority activity for Melbourne Water in estuaries and Parks Victoria in marine and coastal protected areas. But the Understanding the Western Port Environment report indicated It appears that few studies have been undertaken on Spartina in Western Port, and that little is known of its environmental impacts there.

Two marine pest species of concern are already established in Western Port or may spread there in the future. The New Zealand screw shell, Maoricolpus roseus, is already present in Bass Strait. M. roseus has been found in high densities in Point Hicks Marine National Park. Anecdotal evidence suggests that it has reduced the diversity of aquatic fauna at this site.

Foxes and cats are serious predators on shorebirds and beach nesting birds. Foxes remain widespread throughout the region except on French Island. French Island’s fox-free status is now being complemented by a feral cat-eradication program on the island.

Rabbits are also widespread across Western Port’s coastal areas. Wild pigs have been deliberately released on Quail Island by amateur hunters where they have caused extensive damage to saltmarsh.

Climate change

Temperatures in the Western Port catchment are predicted to rise by an average of 1.3˚C by 2040 by modelling for a medium climate change scenario. Declining rainfalls are expected to reduce stream flows but modelling indicates more intense periodic storms will mobilise significantly increased suspended material throughout the system.

Surface water temperature increases by 0.5˚C by 2030 are predicted with a very high degree of confidence. The effects of this on water chemistry and marine animals are uncertain but more extreme temperature days are very likely to damage seagrass and mud flat biota exposed at low tide.

The most serious climate change effects are expected to follow sea-level rise and more frequent storm surges. Climate modeling predicts that severe, once-in-a-century storms could become an annual event by 2070. It is likely that sea level rises will displace saltmarsh with mangroves if there is no room for saltmarsh retreat to higher ground. Loss of habitat for shorebirds and beach nesting seabirds is predicted to be extensive. Increasing and more severe storm surges further increase the risk of shoreline erosion. This has implications for sediment input in the bay and for coastal communities and industries on its coasts. Storm surges with a current return interval of 100 years would have a new average return interval of only 40 or as little as 6 years by 2030, and 20 years and perhaps as low as 1 year by 2070.

Recreation

Recreation pressure is expected to grow as Melbourne’s population grows. The resident population of Western Port’s northern hinterland is predicted to grow from 527,000 in 2021 to 780,000 in 2041. Vehicle and trail bike damage to coastal saltmarsh has been reported from many areas in Western Port. Saltmarsh is slow to recover from these impacts. Parks Victoria spends significant resources controlling and prosecuting illegal vehicle access to intertidal areas and damage continues with little control at sites outside Parks Victoria control.

Disturbance by humans, domestic dogs and recreation activities have been observed to cause reduced feeding and excessive energy use by shorebirds. These are likely to reduce the ability of birds to make return migrations to the northern hemisphere to breed, cause predation or destruction of eggs and nest abandonment.

Recreational fishing catch is significant in Western Port. The growing regional population is likely to place increasing pressure on Western Port’s fisheries. Studies of bait-pumping for ghost shrimp in Western Port indicated slow recovery from changes to target species populations and damage to the entire habitat.

Nutrients

Plant nutrients, nitrogen and phosphorus in run-off from agricultural land account for approximately 60% of nutrient loads to Western Port. Urban run-off contributes the remainder. Total nitrogen loads transported to Western Port range from 400 tonnes in an average year to over 1,000 tonnes in a wet year.

However, there was little evidence of long-term change in nutrient concentrations from the 1970s to 2013. Over 80% of nutrient inputs are estimated to be removed from Western Port on tidal flows. Concentrations and loads declined during the Millennium drought. Under medium-confidence climate scenarios, nutrient discharges may become more episodic; low during longer droughts punctuated by large loads from more severe flood events. Trends to more intensive farming may lead to increased nutrient concentrations in runoff from rural and agricultural land.

Urban areas in the Western Port catchment contribute approximately 14% of the total nutrient loads to the site (report by Melbourne Water 2009). Under future population scenarios to 2030, nitrogen and phosphorus load increases greater than 14% are likely.

Sediments

Sediments and associated poor water quality have been identified as the cause of critical seagrass loss from Western Port between 1970 and the 1990s. The vast majority of catchment derived sediment loads come from rural lands (85%); with agriculture (cropping and dairy) accounting for the largest loads. The dominant sources of fine sediment are channel and gully erosion in the Lang Lang River and, to a lesser extent, the Bunyip River and eroding coastal clay banks, particularly around the Lang Lang area.

The net concentration of suspended solids remained stable between 1984 and 2013. As with nutrients (described above) sediment run-off under future climate predictions may be low during periods of drought but very high during storms and floods.

Total seagrass extent has increased since 1999 in the north and west of Western Port but not in the northeast where loss is associated with increased water turbidity. Continuing land and waterway rehabilitation and stabilisation are essential to solve this problem.

Toxicants

Arsenic, nickel, mercury and organotin have been detected at levels exceeding sediment quality guidelines and pose a moderate risk to ecosystem health in some of Western Port’s estuaries. A study of toxicants in Watson’s estuary found evidence of oestrogen impacts on biota. Pesticides have also been detected in estuarine areas, but not in Western Port’s sediments. Toxicants in Western Port sediments were not judged in 2015 to be at levels likely to cause harm to resident fauna and flora. The chemicals thought to be of most concern for Western Port are heavy metals, pesticides from agricultural runoff and veterinary pharmaceuticals and oestrogens from dairying. Herbicides and oestrogen concentrations and risks in Western Port remain a knowledge gap.

Vision and targets for the future

Vision

The Western Port Ramsar Site Management Plan has the following vision:

To maintain, and, where necessary, improve the ecological character of the Western Port Ramsar Site and promote wise and sustainable use.

The Healthy Waterways Strategy vision is:

Waterways and our bays are highly valued and sustained by an informed and engaged community working together to protect and improve their value.

Regional Catchment Strategy targets

The following long-term targets for Western Port (at the year 2050) will contribute to achieving these visons and help ensure this area remains healthy and prosperous for future generations.

Marine water quality

Water quality in Western Port continues to attain the relevant Environmental Reference Standard, sustains healthy ecosystems, supports fishing, and enables safe swimming at most times.

Marine parks

Churchill Island Marine National Park, French Island Marine National Park, Yaringa Marine National Park and Mushroom Reef Marine Sanctuary are in excellent condition and protected.

Marine habitats

The extent and health of the various marine habitat types in Western Port is retained or improved from 2021 to 2050, including mangrove, seagrass, intertidal sand and mudflats and rocky reef.

Marine pests

Existing damaging marine pest infestations in Western Port (from 2021) are controlled or reduced at 2050, and no significant new marine pests have become established.

Fisheries

The diversity of fish species in Western Port is retained and their populations, including those targeted for recreational and commercial fishing, remain healthy and sustainable.

Ramsar wetlands

The ecological condition of the Western Port Ramsar site is at least maintained from 2021 to 2050.

Pest predator control

Feral cats eradicated on French Island creating an island safe-haven for wildlife.

Partner organisations for the journey ahead

The following organisations formally support the pursuit of the Regional Catchment Strategy’s targets for Western Port. They have agreed to provide leadership and support to help achieve optimum results with their available resources, in ways such as:

- Fostering partnerships and sharing knowledge, experiences and information with other organisations and the community

- Seeking and securing resources for the area and undertaking work that will contribute to achieving the visions and targets

- Assisting with monitoring and reporting on the condition of the area.

Traditional Owners

- Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation

Victorian Government

- Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action

- Melbourne Water

- Environment Protection Authority Victoria (EPA)

- South East Water

- Victorian Fisheries Authority

- Trust for Nature

- Parks Victoria

- South Gippsland Water

- Westernport Water

- Phillip Island Nature Parks

- Sustainability Victoria

- Victorian Environmental Water Holder

- Zoos Victoria

Local Government

- South Gippsland Shire Council

- Cardinia Shire Council

- South East Councils Climate Change Alliance

- City of Casey

- Baw Baw Shire Council

- Bass Coast Shire Council

Non Government

- Marine Mammal Foundation

- Dolphin Research Institute

- The Nature Conservancy

- Conservation Volunteers Australia

- The People and Parks Foundation

- Field Naturalists Club of Victoria

- Victorian National Parks Association

- Native Fish Australia (Vic)

- OzFish Unlimited

- Birdlife Australia

- Western Port Biosphere Reserve Foundation

- Western Port Seagrass Partnership

- Habitat Restoration Fund

Community

- Mornington Peninsula Landcare Network

- Merricks Coolart Catchment Landcare Group

- Mornington Peninsula Koala Conservation

- French Island Landcare Group

- Cardinia Environment Coalition

- Bass Coast Landcare Network

- South Gippsland Landcare Network

- Western Port Catchment Landcare Network

- Westernport Swamp Landcare Group

- Loch-Nyora Landcare Group

- Mt. Lyall Landcare Group

- Poowong & District Landcare Group

- Triholm Landcare Group

Add your organisation as a supporter and partner

If your organisation supports these directions and targets for Western Port, it can be listed as a partner organisation. Adding your organisation to this list will:

- Enable your organisation to list one or more priority projects in the Prospectus which will describe how your priority project will pursue the targets of this Regional Catchment Strategy and potentially make your organisation’s project more attractive to investors by using the strategy to highlight its relevance and value

- Demonstrate your commitment to a healthy and sustainable environment

- Demonstrate the level of community engagement and support for this work.

Priority projects to move forward

Priority projects

There are significant ongoing programs and initiatives undertaken by many organisations that are vital for the management of Western Port. In addition, there are numerous project proposals that, if funded and implemented, can contribute to achieving the Regional Catchment Strategy’s visions and targets for the bay. Project proposals include:

- Western Port Ramsar site coordination proposed Melbourne Water

- A lifeline for Fairy Terns led by Birdlife Australia

- Building Site Action Plans for Migratory Seabirds led by Birdlife Australia

- Community Conservation of the Hooded Plover led by Birdlife Australia

- Seagrass meadows for Western Port proposed by OzFish Unlimited

- Protecting the Ramsar values of Western Port proposed by Mornington Peninsula and Western Port Biosphere Foundation

- Western Port Biosphere Blue Carbon proposed by Mornington Peninsula and Western Port Biosphere Foundation

- City of Casey Ramsar Protection Program led by City of Casey

- Mulloway investigations led by Melbourne Water.

A list of project proposals and their key details can be viewed and sorted on the Prospectus section of this website.

Propose a new priority project

As part of the ongoing development and refinement of this Regional Catchment Strategy, additional priority projects may be considered for inclusion in the Prospectus.

If your organisation supports the directions and targets for this area, and has a project it would like highlighted and supported in this Regional Catchment Strategy, please submit a Prospectus Project Proposal.