The region’s beating heart

Urban Melbourne is the region’s most densely urbanised area. It covers 145,000 hectares; about 10% of the region’s total area.

It is comprised of the cities of Frankston, Greater Dandenong, Knox, Maroondah, Manningham, Banyule, Darebin, Moreland, Moonee Valley, Brimbank, Maribyrnong, Hobsons Bay, Melbourne, Port Phillip, Bayside, Kingston, Stonnington, Glen Eira, Monash, Yarra, Whitehorse and Boroondara.

The problems, aims and feasible outcomes of urban land, water and nature conservation here are different to those in rural and wild landscapes. Intact ecosystems and diverse habitats are largely gone from urban landscapes. Hard-surface runoff, water, air and noise pollution, litter, open space fragmentation, physical damage, weeds, cats and foxes are relentless pressures on what remains.

Melbourne’s public authorities and local councils all express commitments in mission and policy to conserve nature and enhance it as human habitat. But success is not so assured. Urban conservation and loss are decided across hundreds of locations each year in competitions for scarce space and between conflicting demands. Laws and regulations made for species and ecosystem protection in rural and wild environments are often ineffective in urban landscapes.

At the same time, the size and density of Melbourne’s population enables funding for urban conservation schemes that might be unaffordable elsewhere. Examples include the freeway tunnel under the Mullum Mullum Valley, the renewal of the unused Healesville Freeway corridor as parkland, Melbourne Water’s Healthy Waterways program and ambitious plans to grow an urban forest across the city.

A quick look back

The land, coasts and waterways of this area is Kulin Nation country. The Kulin people comprise several indigenous language groups. Archaeological evidence at the Murrup Tamboore site north of Melbourne shows the natural resources of this region were supporting Aboriginal people at least 31,000 years ago and possibly double this time.

Urbanised Melbourne grew rapidly from the arrival of the Port Philip Association’s settlement party in 1835; first east along the Yarra River and north to the heavier soils and grassy woodlands of the Maribyrnong River valley. Later, 19th Century housing and market gardens spread south on the sandy soils and easily cleared heathland on Port Phillip Bay’s eastern coast. Melbourne’s population reached 490,000 in 1890.

Access to Melbourne’s port, water supply and wastewater disposal in the Yarra estuary led early development west of the river. But the open plain west of Melbourne offered little attraction or shelter, poor soils, few streams and sparse rainfall. It saw little urban development for another 60 years.

Melbourne’s population reached 1 million around 1930. Its suburbs spread north and repurposed the Yarra’s tributaries, Moonee Ponds Creek, Merri Creek, Darebin Creek and the Plenty River as urban drains.

Post-war industry took advantage of the low-cost, flat land on the western plains. Factories, warehouses, rail yards and new suburbs helped make the Melbourne region’s once vast and abundant native grasslands into a critically endangered vegetation type.

Melbourne’s population reached 2 million in 1963. By the end of the 1970s, most of the Eucalyptus forest and grassy woodlands, east and north-east to the Yarra Valley and the Dandenong Ranges were gone. And the last of fifty square kilometres of the Carrum Carrum swamp along Port Phillip’s eastern shore were finally drained for farms, new bayside suburbs and the Patterson Lakes marinas.

The condition of our environment now

The Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation and the Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation now continue as Traditional Owners to practice and strengthen their culture, heritage and care for this Country. There is increasing recognition, respect and support for Bunurong and Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung people to protect, reintroduce and strengthen their cultural heritage.

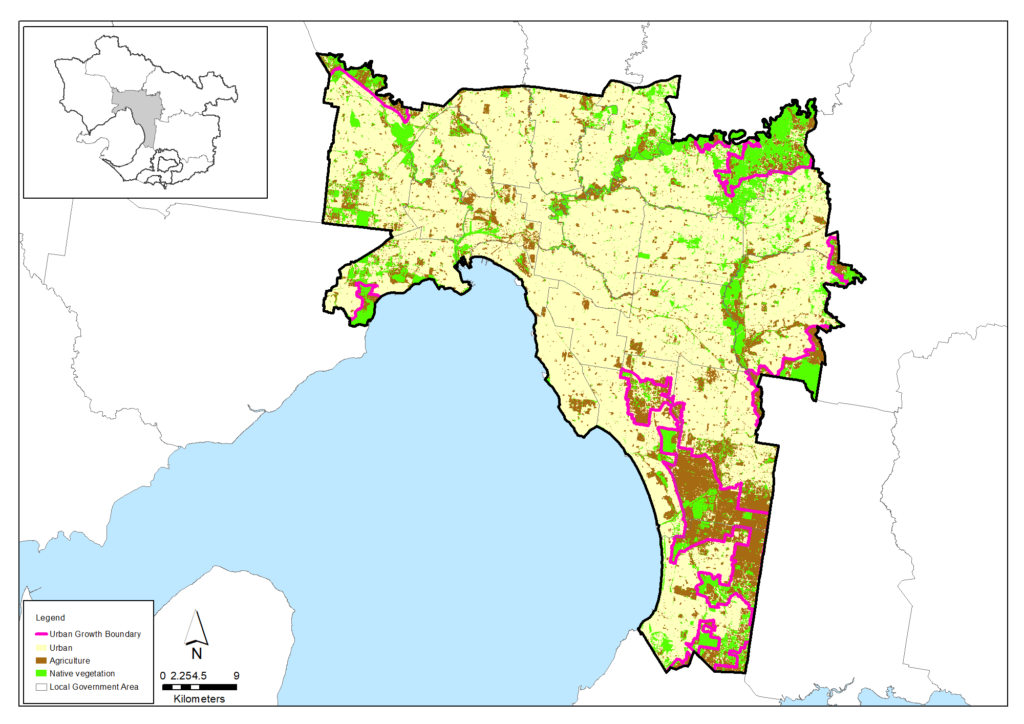

Land use

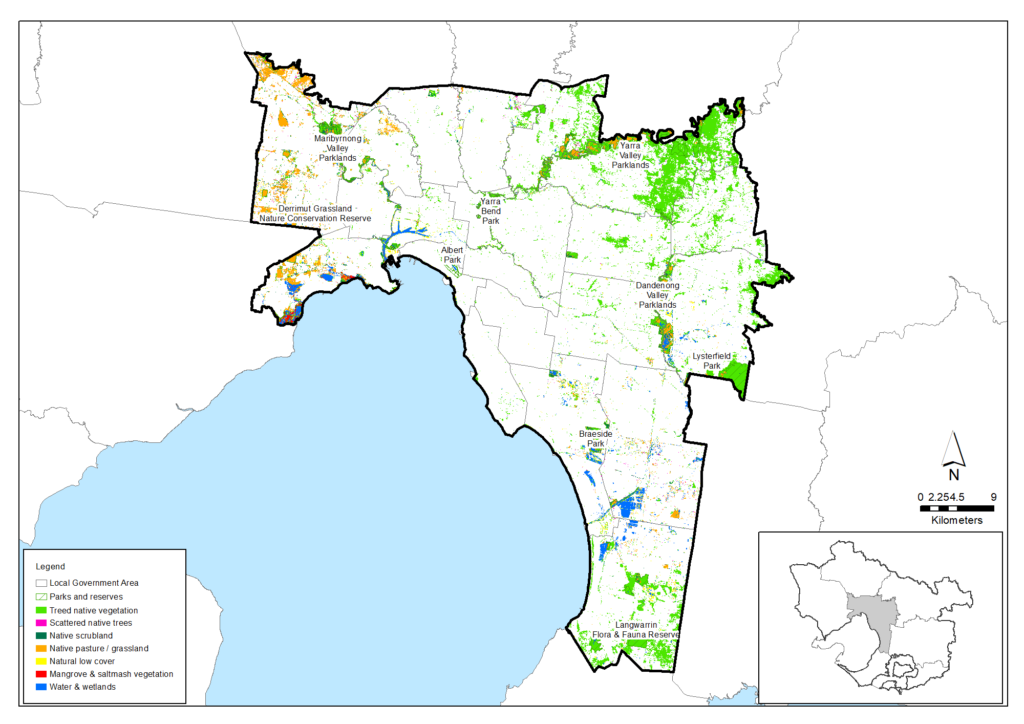

Urban Melbourne’s landscapes have been irreversibly changed. Around 100,000 hectares, 69% of the area, is urban or built infrastructure while only approximately 22,000 hectares or 15% of the area retains native vegetation cover. The native vegetation cover falls to around 2% in inner city suburbs.

Relatively little vegetation cover in Urban Melbourne is protected – there are only 3,970 hectares of public parks and gardens in the Urban Melbourne area. The dominance of private land in the urban area makes vegetation conservation difficult to coordinate and enforce.

Waterways

The Lower Yarra is the dominant waterway in Urban Melbourne area. But the lower reaches of the Kororoit, Laverton and Skeleton Creeks rise in the Werribee catchment and flow through the Urban Melbourne area into the northwest corner of Port Phillip Bay.

Urban Melbourne’s rivers and creeks are the lower reaches of most of the region’s 25,000 kilometres of waterways. The values and qualities of Urban Melbourne’s waterways are most impaired here by the demands of urbanisation and rural land uses for development and drainage and their effects on water flows and quality.

While waterway environments in the Urban Melbourne area are biologically impaired, they are very important for other values such as amenity, community connection and recreation. The Healthy Waterways Strategy aims to strengthen these social values and pursue improvements for their biological states.

Biodiversity

Only around 15% of the Urban Melbourne area retains native vegetation now.

The diversity of native animal species has declined in this area in response to urbanisation, habitat loss, pest predation and other factors, as indicated in an analysis of animal sighting data that calculated the probability that each species of native birds, mammals, amphibians, reptiles and fish was persisting at the end of 2016.

However, the analysis indicated that, for the Urban Melbourne area, around 77% of the total number of species recorded here are still persisting. In general, birds and reptiles seem to have fared the best whereas native fish and mammal species seem to been more affected.

| Native species | Number and proportion of species likely to be persisting (at 2016) |

|---|---|

| Birds | 303/374 (81%) |

| Mammals | 29/49 (59%) |

| Amphibians | 15/20 (75%) |

| Reptiles | 33/39 (82%) |

| Fish | 18/32 (56%) |

| Total | 397/514 (77%) |

Threatened species are considered to be priorities for local protection and recovery work. In many circumstances, work to protect and enhance their health and resilience will also benefit other native animal species and the local habitat. The following table shows some of the threatened species and ecological communities that have been recorded in this area. A full list of the threatened species known to occur in this region since 1980 is available at the Data tables section of this strategy.

Threatened species known to occur in the Urban Melbourne area

| Group | Species |

|---|---|

| Birds | Australasian Bittern, Australian Little Bittern, Australian Painted Snipe, Barking Owl, Bar-tailed Godwit, Black Falcon, Blue-billed Duck, Brolga, Caspian Tern, Curlew Sandpiper, Diamond Firetail, Eastern Curlew, Eastern Great Egret, Fairy Tern, Freckled Duck, Great Knot, Grey Goshawk, Hooded Plover, Lewin's Rail, Little Egret, Little Tern, Magpie Goose, Major Mitchell's Cockatoo, Masked Owl, Northern Giant Petrel, Orange Bellied Parrot, Painted Honeyeater, Plumed Egret, Powerful Owl, Red Knot, Regent Honeyeater, Sooty Owl, Southern Giant Petrel, Speckled Warbler, Square-tailed Kite, Swift Parrot, White-bellied Sea-Eagle, White-throated Needletail |

| Mammals | Brush-tailed Phascogale, Eastern Barred Bandicoot, Eastern Bent Winged Bat, Greater Glider, Grey-headed Flying-fox, Southern Brown Bandicoot, Swamp Antechinus, White-footed Dunnart, Platypus |

| Reptiles | Broad-shelled Turtle, Striped Legless Lizard, Swamp Skink, Lace Monitor, Tussock Skink |

| Amphibians | Brown Toadlet, Growling Grass Frog, Southern Toadlet |

| Fish | Australian Grayling, Dwarf Galaxias, Freshwater Catfish, Macquarie Perch, Murray Cod, Trout Cod |

| Invertebrates | Eltham Copper Butterfly, Golden Sun Moth |

| Flora | Bacchus Marsh Wattle, Basalt Pepper-cress, Button Wrinklewort, Clover Glycine, Gully Grevillea, Large-flower Crane’s-bill, Large-fruit Yellow-gum, Large-headed Fireweed, Maroon Leek-orchid, Matted Flax-lily, Pale Myoporum, Plains Rice-flower, Purple Blown-grass, Purple Diuris, Short Water-starwort, Silver Gum, Small Golden Moths Orchid, Small Milkwort, Sunshine Diuris, Swamp Everlasting, Tough Scurf-pea, Yellow Elderberry, Yellow-lip Spider-orchid, Christmas Spider-orchid, Kilsyth South Spider-orchid, Large-flower Crane's-bill, Spiny Rice-flower, Small Scurf-pea, Basalt Sun-orchid, Melbourne Yellow-gum, Buloke |

| Ecological communities | Grassy Eucalypt Woodland of the Victorian Volcanic Plain, Grey Box (Eucalyptus microcarpa) Grassy Woodlands and Derived Native Grasslands of South-eastern Australia, Natural Damp Grassland of the Victorian Coastal Plains, Natural Temperate Grassland of the Victorian Volcanic Plain, Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands (Freshwater) of the Temperate Lowland Plains, Subtropical and Temperate Coastal Saltmarsh, White Box-Yellow Box-Blakely's Red Gum Grassy Woodland and Derived Native Grassland, Central Gippsland Plains Grassland, Forest Red Gum Grassy Woodland, Grey Box - Buloke Grassy Woodland Community, Herb-rich Plains Grassy Wetland (West Gippsland), Rocky Chenopod Open Scrub, Western (Basalt) Plains Grasslands, Western Basalt Plains (River Red Gum) Grassy Woodland |

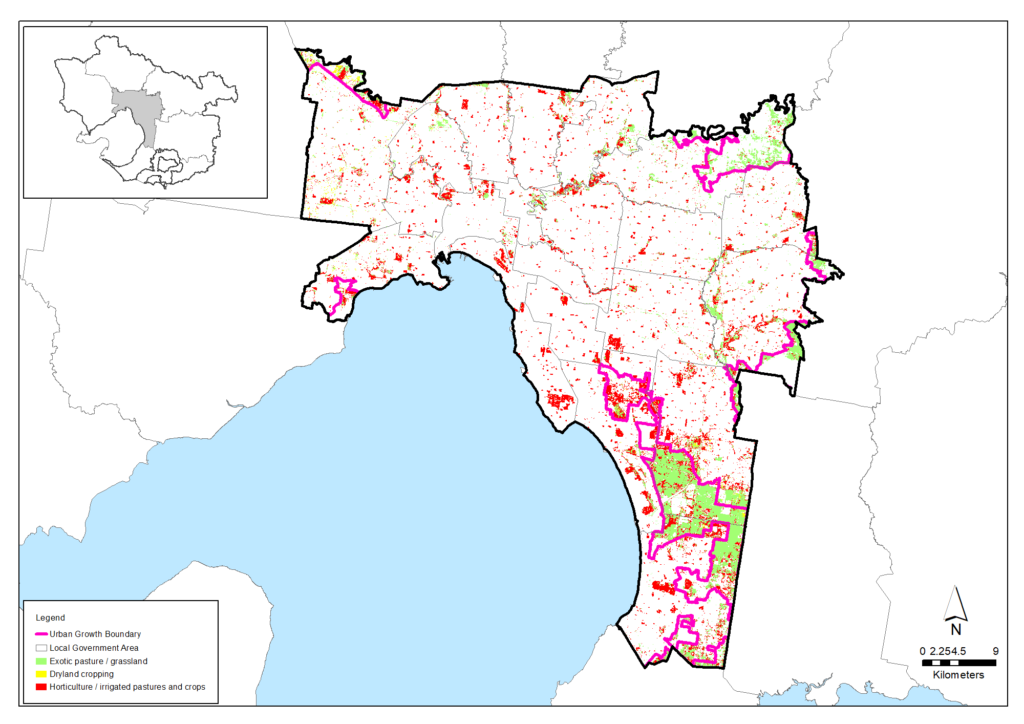

Agriculture

Agriculture persists in the Urban Melbourne Area on around 156 professional enterprises. Commodities worth $84 million were grown in 2015-16, mostly vegetables, cut flowers and other plant nursery products.

The agricultural enterprises persist mainly in the defined Green Wedges that jut into the Urban Melbourne area. The value of the Green Wedges goes well beyond the agricultural production from these areas. The Green Wedges provide open space, biodiversity, semi-rural vistas, cooling and other benefits for Melbourne and its residents.

The value of open space and food production close to Melbourne has been particularly highlighted in the global pandemic of 2020-21, underlining the importance of the Victorian Government’s Planning for Melbourne’s green wedges and agricultural land that is underway to ensure these areas are protected and supported for future generations.

| Agriculture data from 2015-16 | Bass Coast, South Gippsland & islands |

|---|---|

| Area of Urban Melbourne (Hectares) | 145,391 |

| Area of agriculture (Hectares) | 23,233 (16%) |

| Number of farms | 156 |

| Employment on farms | 8,655 |

| Gross value of annual agricultural production ($) | $84 million |

| Main agricultural commodities | Vegetables, nurseries |

Groundwater resources of commercial quality and volume are concentrated in three parts of the Urban Melbourne area; the Cut Paw Paw, Moorabbin and Frankston Groundwater Management Units (GMUs). Irrigation, industrial and commercial uses account for most demand. Groundwater use in the Urban Melbourne area is well below permissible volumes. 45% of permissible volume was extracted from the Moorabbin GMU in 2018-19. Use in the Frankston and Cut Paw Paw GMUs took barely 6% of permissible volumes.

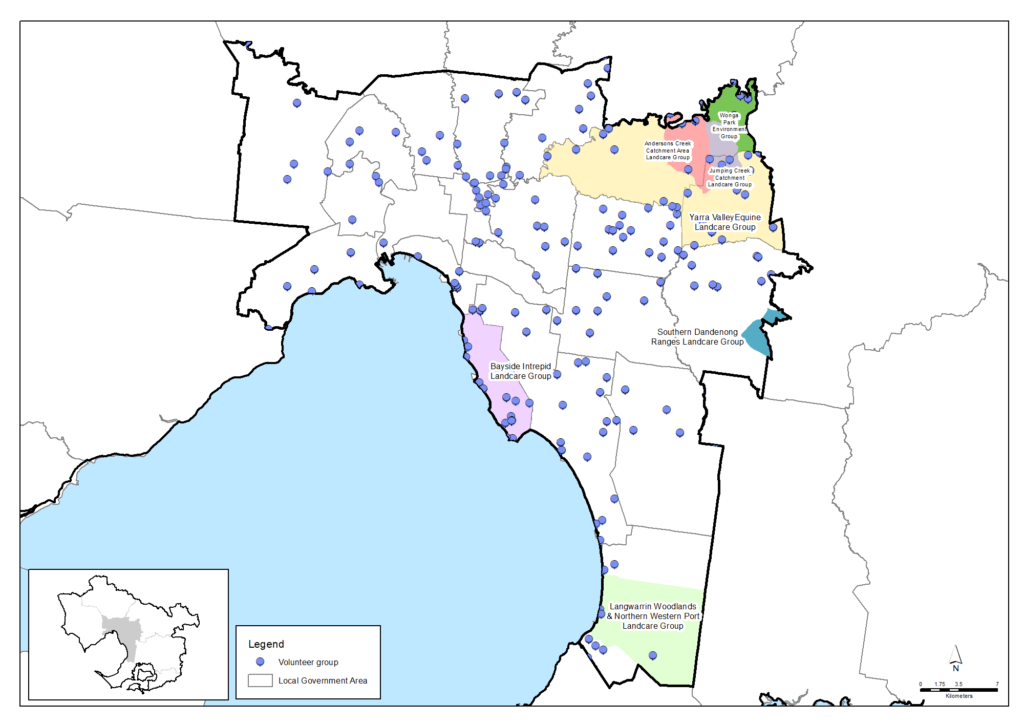

Community action

Community volunteerism in natural resource management is significant though offers potentially much greater value if more of the 5 million resident population can be engaged and mobilised.

Though the area is predominantly urban, there is also significant rural land and bush land in this area. The Middle Yarra Landcare Network and its member groups including Andersons Creek Landcare Group, Jumping Creek Catchment Landcare Group, Friends of Yarra Valley Parks and Wonga Park Environment Group are particularly active in the rural fringe of the Manningham Council area. Based on data from a 2019 survey, it is estimated that the Landcare groups and networks collectively have around 132 members and volunteer around 5,548 hours per year for Landcare activities that benefit the environment, landscapes and community. This volunteering is worth in the order of $187,023 per year.

Community volunteers are also active in numerous Friends groups, Committees of Management and other volunteer organisations across the sub-region. There are an estimated 191 organisations providing 194,277 volunteer hours worth $6,549,078 per year.

Community lobby groups are major forces in environmental decision-making in the urban area. These groups are active environmental advocates in the competition for space between environment and development.

More detail is in the Community volunteering data table.

Challenges we face

Population growth

Urbanisation replaces vegetated surfaces with hard impervious surfaces (such as roofs, roads and paved areas) that drain directly into waterways via stormwater systems. This increases runoff (changed water flow rates) and reduces water quality. Urbanisation also results in altered waterway structure, with a straightening of rivers, draining of wetlands, opening of estuaries and vegetation clearance.

Population growth and applications for development will continue to create pressure for clearing at other areas. In addition, incremental damage to native vegetation from recreation, illegal clearing, vandalism and rubbish dumping are inevitable pressures of increasing resident and visitor populations.

Native vegetation decline

Increasing housing and population density in the Urban Melbourne area will continue to drive vegetation loss through clearing of remnant vegetation patches and individual trees on private land. Accompanying infrastructure development will continue these losses, especially on public land. Space constraints in the Urban Melbourne area make these losses difficult to replace locally. Most are offset on distant rural sites.

Waterway health

The Healthy Waterways Strategy shows that continuing urbanisation and climate change is likely to drive another 850 kilometres of the whole region’s waterways into ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’ condition over the next 50 years. Preventing further ecological decline in urban waterways is a major challenge. Improving waterway values for amenity, recreation and community connection will be more achievable, priority goals in the Urban Melbourne area.

Climate change

A dryer, warmer climate, more frequent and intense heatwaves and droughts will stress all plants and animals and the ecological connections that sustain them. Existing pressures on land, water and nature are predicted to multiply and become more complicated. Conservation efforts may only be able to influence the development of new desirable states.

Important environmental assets in the Urban Melbourne area with conditions and values likely to be threatened by climate change include:

- Native vegetation in the Yarra River and Maribyrnong River corridors

- Coastal wetlands at Laverton and Altona

- Ramsar freshwater wetlands between Edithvale and Seaford

- Soils between Mordialloc and Frankston sensitive to rising sea levels and saltwater intrusion.

The urban heat island effect will be an issue for Melbourne. Current development of growth areas to support Melbourne’s future population will see more people exposed to extreme urban heat levels and significantly increase the number of heat-vulnerable communities.

Climate Risk Assessments developed by the three Local Government-based Alliances for Greenhouse Action, the Eastern Alliance, the Northern Alliance and the Western Alliance and work by the South East Councils Climate Change Alliance indicate:

- Vulnerability to climate change is compounded for newly arrived migrants, the aged and young children and people living in relative poverty, in sub-standard housing or with poor English

- Lack of understanding of local flora and fauna species responses to climate change is hampering timely and effective investment and action for biodiversity conservation

- Social and policy pressures for larger fire breaks and more fuel-reduction burning is impacting biodiversity and air quality

- Changing wildfire frequency and intensity in warmer, drier conditions is damaging biodiversity and increasing demands for fire-management effort

- Fire agency management planning often conflicts with the environmental protection goals and targets of local, regional and state environment strategies.

Weeds and pests

Environmental weeds spread in the urban area from domestic gardens and from garden waste dumped into bush and waterway reserves. Environmental weeds grow vigorously and have few natural predators or diseases. They outcompete native plants for space, light, nutrients and water and degrade habitats for native animals.

Foxes and domestic cats are significant predators in the urban area. They are a major cause of decline and extinction among native mammals, reptiles and birds.

Introduced fish such as Mosquito Fish compete for food and prey on native fish, tadpoles and frogs. European Carp are common in urban waterways. Their foraging habits damage native fish habitat and water quality.

Supporting Bunurong and Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung connection with Country

There is a challenge to strengthen the role and influence of traditional ecological knowledge and practices in today’s natural resource management programs, where that is allowed and offered by Traditional Owners.

There are currently relatively few Aboriginal people who have jobs taking care of Country in this region, with the exception of some outstanding examples such as the Wurundjeri Narrap Team. There is a challenge in providing timely, tailored support for Registered Aboriginal Parties and other Aboriginal organisations so they can determine their aspirations and build their workforce to suit their aims with the appropriate range of skills.

Traditional Owners’ rights to water have largely been excluded from water planning and management policies and programs. Without water rights, Traditional Owners are unable to decide where or how water can be used to support cultural, spiritual, environmental or economic outcomes. There is an opportunity to address this in water planning and securing water allocations for Registered Aboriginal Parties to enable cultural watering.

Policy and planning

Plan Melbourne 2017-2050 is the main integrated land-use, infrastructure and transport plan published by the Victorian Government. It aims to support economic growth and protect liveability and sustainability across metropolitan Melbourne. As part of its implementation, Land Use Framework Plans are being developed to guide strategic land-use and infrastructure development for the next 30 years for the following six metropolitan Melbourne regions:

- Inner (Melbourne, Port Phillip and Yarra Local Government Areas)

- Inner South East (Bayside, Boroondara, Glen Eira and Stonnington)

- Eastern (Knox, Manningham, Maroondah, Monash, Whitehorse and Yarra Ranges)

- Southern (Cardinia, Casey, Frankston, Greater Dandenong, Kingston and Mornington Peninsula)

- Western (Brimbank, Hobsons Bay, Maribyrnong, Melton, Moonee Valley and Wyndham)

- Northern (Banyule, Darebin, Hume, Mitchell, Moreland, Nillumbik and Whittlesea).

For Melbourne’s urban growth areas, the Victorian Planning Authority manages the development of Precinct Structure Plans (PSPs) which are master plans for local areas that usually cater for between 5,000 to 30,000 people, 2,000 to 10,000 jobs or a combination of both. PSPs provide more specific detail regarding how existing important features of local communities such as roads, shopping centres, schools, parks, key transport connections and areas for housing and employment may evolve or transform over time and become better integrated.

The management of land, water and biodiversity in the Urban Melbourne area is principally overseen by the Councils, Melbourne Water, Parks Victoria, the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action and EPA Victoria, along with landholders and other authorities, organisations and community groups. Each has policies and plans to protect and improve environments.

Council Plans are being developed by each council in 2021. The plans will be the major strategic document outlining what each Council is planning to achieve in the subsequent four years (as part of its longer term journey) and how it will achieve those outcomes. In addition to the Councils Plans, key strategies or plans relevant to natural resource management for each Council can be accessed below. These may include links to other plans for specific local environments and sites. Some Council areas, including those around the urban fringe such as Manningham, Banyule, Maroondah, Frankston, Brimbank and Hobsons Bay have significant areas of rural land, bushland, wetlands and good quality waterways that are important both locally and from a regional perspective.

The Victorian Government has also developed Open Space for Everyone as a blueprint for planning and managing Melbourne’s open space network. It aims to foster coordinated decision-making and action by governments, Traditional Owners, communities, researchers and business to protect existing open space and use a wide variety of public lands for new parks and trails.

Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037 is the Victorian Government’s statewide strategy to arrest biodiversity decline. It describes goals for community awareness through connection with nature and for physical habitat protection and improvement.

In response to growing pest animal issues, including deer, the Eastern Region Pest Animal Strategy 2020-2030 has been developed by the Eastern Region Pest Animal Network.

The Healthy Waterways Strategy 2018-28 provides vision statements and 10 and 50-year targets for waterway management in each of the region’s five major catchments (Werribee, Maribyrnong, Yarra, Dandenong and Westernport). The Urban Melbourne area contains the lower reaches of streams in the Maribyrnong, Yarra and Dandenong catchments.

Planning for Melbourne’s green wedges and agricultural land is underway by the Victorian Government to ensure these areas are protected and supported for future generations. The Government’s intention to permanently protect Melbourne’s green wedges and vital agricultural land from inappropriate use and development remains strong and community consultation has been undertaken to determine priority ways to achieve this. Implementation of planning reforms is expected to commence in the second half of 2021.

Climate Risk Assessments have been developed by the three Local Government-based Alliances for Greenhouse Action, the Eastern Alliance, the Northern Alliance and the Western Alliance and an Asset Vulnerability Assessment and Community Climate Change Action Plan is also under way by the South East Councils Climate Change Alliance.

Living Melbourne: our metropolitan urban forest aims to grow an urban forest across the city to strengthen the benefits of clean air and water, temperature moderation and wildlife habitat in the urban area.

Traditional Owners are the voice of their Country

For all policy and planning, there is a need for recognition and inclusion of Traditional Owner knowledge and aspirations. The waterways and lands are increasingly being recognised as ‘living and integrated natural entities‘ and the Traditional Owners should be recognised as the ‘voice of these living entities’. Country Plans are being prepared by the Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation and the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation and will describe the vision and priorities of the Traditional Owners for Country under their roles as Registered Aboriginal Parties, and provide a strong basis for all planning to recognise and include the voices of these Traditional Owners.

Vision and targets for the future

Vision

The Traditional Owners of this area, the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung and Bunurong peoples, have cared for this Country for tens of thousands of years. Visions for their respective Country will be outlined in the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Country Plan (in preparation) and the Bunurong Country Plan (in preparation).

Plan Melbourne 2017-2050 includes a vision for Melbourne as “A global city of opportunity and choice” underpinned by nine principles including Principle 4 that states:

Environmental resilience and sustainability – Protecting Melbourne’s biodiversity and natural assets is essential for remaining a productive and healthy city.

Living Melbourne: our metropolitan urban forest, a collaboration of many Councils, Government and other organisations in and around Melbourne, aims to grow an urban forest across the city to strengthen the benefits of clean air and water, temperature moderation and wildlife habitat in the urban area, with the following broad vision:

Our thriving communities are resilient, connected through nature.

Regional Catchment Strategy targets

The following long-term targets for the Urban Melbourne area (at the year 2050 or further) reflect the visions and directions of the Regional Catchment Strategy and the strategies outlined above, along with those of the local councils, the Healthy Waterways Strategy, other plans and the community. Pursuing these targets at local scale will contribute to the regional and state-scale targets outlined in the ‘Themes‘ section of this strategy.

Water

Water supply and use

Adequate and stable water supplies have been secured for households, businesses, farms, Traditional Owners and the environment across the Urban Melbourne area. Water is shared, distributed and used efficiently by all users.

.

Water for the environment

The environmental water reserve has been increased by at least 15-25 GL/yr in the Yarra catchment and 10-20 GL/yr in each of the Maribyrnong and Werribee catchments, and an average score for environmental water of HIGH has been achieved across each catchments.

.

Water for Traditional Owners

Significant water allocations in Urban Melbourne have been secured for Traditional Owners to enable cultural watering.

Water for agriculture

Use of recycled water and stormwater have boosted agricultural water supply and security in the Yarra Ranges & Nillumbik area.

Fish in waterways

Achieve an average score for fish in waterways of MODERATE for the Werribee, Maribyrnong and Dandenong catchments and HIGH for the Yarra catchment, including for Urban Melbourne waterways.

Waterway amenity

Achieve an average score of HIGH for waterway amenity across the Werribee and Maribyrnong catchments and VERY HIGH across the Dandenong and Yarra catchments, including for Urban Melbourne waterways.

Vegetation extent along waterways

Achieve an average score of HIGH for vegetation extent along waterways in the Yarra, Maribyrnong and Werribee catchments, and MODERATE for the Dandenong catchment, including for Urban Melbourne waterways.

Vegetation quality along waterways

Achieve an average score of MODERATE for vegetation quality along waterways in the Dandenong, Maribyrnong and Werribee catchments, and HIGH for the Yarra catchment, including for Urban Melbourne waterways.

Wetlands water regime

Achieve an average score of at least LOW for wetlands water regime in the Maribyrnong and Werribee catchments, MODERATE in the Dandenong catchment and HIGH in the Yarra catchment.

Wetlands vegetation

Achieve an average score for wetland vegetation condition of MODERATE for the Dandenong, Maribyrnong and Werribee catchments and HIGH for the Yarra catchment.

Wetlands water quality

Achieve an average score for wetlands water quality of at least LOW for the Dandenong, Maribyrnong and Werribee catchments and MODERATE for the Yarra catchment.

Ramsar wetlands

The ecological condition of the Port Phillip Bay (western shoreline) Ramsar wetland and Edithvale-Seaford Ramsar wetland are at least maintained from 2021 to 2050.

Groundwater supply and use

Groundwater licences and annual use kept within the Permissible Consumptive Volume for the Cut Paw Paw, Moorabbin & Frankston Groundwater Management Units to ensure sustainable supply.

Groundwater quality

Groundwater quality in the Cut Paw Paw, Moorabbin & Frankston Groundwater Management Units maintained at sufficient standard to enable ongoing groundwater use.

Biodiversity

New parks

At least 6,500 hectares of new suburban parks established in the Urban Melbourne area between 2021 and 2027.

.

Permanent protection

Around 160 hectares of new permanently protected vegetation areas established on private land across the Urban Melbourne area between 2017 and 2050 (an average of at least 5 hectares per year).

.

Revegetation

Around 830 hectares of revegetation established at priority locations for habitat connectivity across the Urban Melbourne area between 2017 and 2050 (an average of at least 25 hectares per year).

Major new biolinks

Numerous major biolinks established, including along river corridors, providing vegetation links or effective ‘stepping stones’ between major parks and habitats.

Pest and weed control

Sustained pest herbivore control achieved and maintained for at least 2,000 hectares and sustained weed control achieved and maintained for at least 3,000 hectares in priority areas of the Urban Melbourne area between 2017 and 2050.

Threatened vegetation

All threatened native flora species and ecological communities that are present in the Urban Melbourne area in 2021 are retained in 2050 and are sustainable, secure, healthy and resilient.

Diversity of native animals

The diversity of native animal species that inhabit the Urban Melbourne area in 2021 are retained in 2050.

Threatened animals

Wild populations of all threatened native animal species that are present in the Urban Melbourne area in 2021 are retained in 2050 and their populations are sustainable, secure, healthy and resilient.

Pest predator control

Sustained pest predator control achieved and maintained for at least 500 hectares in priority areas of the Urban Melbourne area between 2017 and 2050.

Land

Land use

While planned urban development has progressed, the extent and quality of native vegetation, significant landscapes, cultural heritage values and environmental assets have been retained. Significant infrastructure, extractive resources, open space areas and agriculture have been carefully planned for and protected. Sufficient extent and quality of native vegetation and agriculture is retained, including in the Green Wedges, to support healthy ecosystems and agricultural industries.

.

Land for agriculture

The green wedges in the Urban Melbourne area (including the South East, Manningham, Yarra Valley and Yarra and Dandenong Ranges, Southern Ranges, Sunbury, Werribee South and Mornington Peninsula Green Wedges) are retained for agricultural use and are supporting diverse and profitable agricultural enterprises.

.

Sustainable agriculture systems

The farms and agricultural industries in the area are recognised as leaders in agri-ecological sustainability and resilience.

Agricultural production

Diverse agriculture remains a feature of the Urban Melbourne area. The gross value of agriculture production has grown at an average of over 5% per year from 2021 to 2050 to exceed $380 million, and employment in agriculture has trended steadily upwards from the 2019 level of around 8,600 people in this area.

Coasts and marine

Coastal vegetation

The coastal zones of the Urban Melbourne area retain at least 80-90% of their area as native vegetation.

.

Estuarine flow regime

Achieve an average score for estuarine flow regime of at least LOW for the Dandenong and Maribyrnong catchments, MODERATE for the Werribee catchment and HIGH for the Yarra catchment.

.

Estuarine vegetation

Achieve an average score for estuarine vegetation of at least LOW for the Dandenong, Yarra and Maribyrnong catchments and MODERATE for the Werribee catchment.

Traditional Owners

Traditional Owners as the ‘voice’ for waterways and Country

Traditional Owners are the strong and respected voice for Country, with fundamental roles and influence in planning, decision making and action across the region in land, biodiversity and water management. The value of traditional ecological knowledge held by the region’s Traditional Owners is embraced and influential in modern decisions and practices.

.

Cultural heritage sites

Aboriginal cultural heritage sites are formally registered and protected across the Urban Melbourne area, and Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung and Bunurong representatives are involved in the care and preservation of key cultural heritage sites. More importantly, the recognition of cultural heritage has evolved to include intangible values (such as cultural practices, knowledge and oral traditions) and the continuous connection embodied in the concept of “Country”.

.

Indigenous representation in natural resource management

All major natural resource management planning forums and processes relevant to the Urban Melbourne area include Indigenous representation and recognise the Traditional Owners as the voice for their Country.

Communities

Landcare group health

Landcare groups in the Urban Melbourne area maintain an average group health score of at least 3.7/5.

..

Community volunteering

At least 540,000 hours of community volunteering is contributing to natural resource management each year in the Urban Melbourne area (up from approx. 430,000 hours in 2019).

Climate change

Carbon emissions

Victoria has achieved net zero emissions. All local water corporations have achieved net zero emissions. The local agriculture sector has contributed to the achievement of this economy-wide net zero emissions target.

.

Cooling, greening Melbourne

Total tree canopy and shrub cover for metropolitan Melbourne areas has increased to at least:

– Western 30%

– Northern 39%

– Inner 33%

– Southern 50%

– Inner South-East 50%

– Eastern 50%.

.

Climate change adaption

Organisations, communities and individuals have responded effectively to the challenges of climate change, minimising the negative impacts on ecological, social and economic well-being.

Partner organisations for the journey ahead

The following organisations formally support the pursuit of the Regional Catchment Strategy’s targets for the Urban Melbourne area. They have agreed to provide leadership and support to help achieve optimum results with their available resources, in ways such as:

- Fostering partnerships and sharing knowledge, experiences and information with other organisations and the community

- Seeking and securing resources for the area and undertaking work that will contribute to achieving the visions and targets

- Assisting with monitoring and reporting on the condition of the area.

Traditional Owners

- Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation

Local Government

- Monash City Council

- Bayside City Council

- Hobsons Bay City Council

- Kingston City Council

- City of Stonnington

- Glen Eira City Council

- City of Port Phillip

- Maroondah City Council

- Manningham City Council

- Northern Alliance for Greenhouse Action

- City of Melbourne

- City of Greater Dandenong

- Whitehorse City Council

- Knox City Council

- Brimbank City Council

- Moonee Valley City Council

- Eastern Region Pest Animal Network

- Western Alliance for Greenhouse Action

- South East Councils Climate Change Alliance

- Eastern Alliance for Greenhouse Action

Community

- Port Phillip EcoCentre

- NatureWest

- Hobsons Bay Wetlands Centre Inc.

- Werribee River Association

- Friends of Lower Kororoit Creek Inc

- Darebin Creek Management Committee

- Yarra Riverkeeper Association

- Friends of Dandenong Valley Parklands

- Kooyongkoot Alliance

- Rewilding Stonnington

- Abbotsford Riverbankers Inc

- Merri Creek Management Committee

Victorian Government

- Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action

- Melbourne Water

- Parks Victoria

- Yarra Valley Water

- South East Water

- Zoos Victoria

- Environment Protection Authority Victoria (EPA)

- Victorian Planning Authority

- Victorian Fisheries Authority

- Trust for Nature

- Sustainability Victoria

- Victorian Environmental Water Holder

Non Government

- Dolphin Research Institute

- The Nature Conservancy

- Birdlife Australia

- Gardens for Wildlife Victoria

- Field Naturalists Club of Victoria

- Conservation Volunteers Australia

- Native Fish Australia (Vic)

- OzFish Unlimited

- The People and Parks Foundation

- Habitat Restoration Fund

Add your organisation as a supporter and partner

If your organisation supports these directions and targets for the Mornington Peninsula, you can request to be listed as a partner organisation. Adding your organisation to this list will:

- enable your organisation to list one or more priority projects in the Prospectus which will describe how your priority project will pursue the targets of this Regional Catchment Strategy and potentially make your organisation’s project more attractive to investors by using the strategy to highlight its relevance and value

- demonstrate your commitment to a healthy and sustainable environment

- demonstrate the level of community engagement and support for this work.

Priority projects to move forward

Priority projects

There are significant ongoing programs and initiatives undertaken by many organisations that are vital for the management of natural resources and the support of communities in the Urban Melbourne area. In addition, there are numerous project proposals that, if funded and implemented, can contribute to achieving the Regional Catchment Strategy’s visions and targets for the area. They include projects that:

- Establish new vegetation in strategic locations where it provides multiple benefits by contributing to carbon sequestration, habitat restoration and habitat connectivity

- Help achieve net gain in the extent and condition of habitat across public and private land, coasts and waterways

- Protect waterways

- Protect threatened species

- Support the retention of Melbourne’s Green Wedges and the adoption of sustainable agriculture practices

- Support resilience to climate change

- Increase community participation, engagement, education and enjoyment in nature and conservation

- Strengthen Traditional Owners roles in environmental decision-making and action.

Project proposals include:

- Living Links Partnership proposed by Melbourne Water

- Farms2Schools proposed by Melbourne Water

- Reimagining your Moonee Ponds Creek led by Melbourne Water

- Lower Dandenong Creek Litter Collaboration led by Melbourne Water

- Patterson River Litter Trap led by Melbourne Water

- Merri Creek Biolink led by Merri Creek Management Committee

- Merri Creek Community Engagement led by the Merri Creek Management Committee

- Moonee Ponds Creek Litter Action led by the Chain of Ponds Collaboration

- Eltham Copper Butterfly Habitat Restoration proposed by Melbourne Water

- Sydenham Park led by Brimbank City Council

- Elsternwick Park led by Bayside City Council

- Port Phillip Wildlife Corridors led by the City of Port Phillip

- Regenerating Gardiners Creek (Kooyongkoot) led by Stonnington City Council

- Hobsons Bay wetlands centre proposed by Hobsons Bay Wetlands Centre Inc.

- Inclusive conservation of Wetlands proposed by Birdlife Australia

- Native fish tanks in schools led by Native Fish Australia (Victoria)

- Marine Litter Project led by the Marine Mammal Foundation

- Fish habitat in the Maribyrnong River proposed by OzFish Unlimited

- Growing Dandenong Biodiversity led by the City of Greater Dandenong

- Connecting to Country led by the City of Greater Dandenong

- Victorian Climate Resilient Councils proposed by the Western Alliance for Greenhouse Action

- Mordialloc Creek Rehabilitation and Wetlands Project led by Melbourne Water.

A list of project proposals and their key details can be viewed and sorted on the Prospectus section of this website.

Propose a new priority project

As part of the ongoing development and refinement of this Regional Catchment Strategy, additional priority projects may be considered for inclusion in the Prospectus.

If your organisation supports the directions and targets for this area, and has a project it would like highlighted and supported in this Regional Catchment Strategy, please submit a Prospectus Project Proposal.