The importance of native vegetation

The diversity, extent and quality of native vegetation is a cornerstone for the health and resilience of ecosystems and all of the living things within them. As natural habitat, it supports our native animal species including the threatened species of the area.

But native vegetation does much more than that; it also provides other environmental, social and economic benefits. For example, native vegetation sequesters carbon to combat climate change and has a cooling effect in cities and landscapes, filters water to benefit water quality, helps to control soil erosion and reduce flood impacts, provides attractive natural areas with amenity and human health and wellbeing benefits, and supports nature-based recreation and tourism. In fact, Victoria’s natural environment is our biggest tourist attraction.

Rich though it remains today, the native vegetation of Victoria has been under sustained pressure for nearly two centuries and is not as extensive, diverse or healthy now as it once was. Victoria is the most intensively settled and cleared state in Australia, with more than 50% of the state’s native vegetation cleared. This has enabled Victoria to become a powerhouse of agricultural production, with huge benefits to the state economy, but it has also left a legacy of loss, degradation and fragmentation of habitats that is evident across the state. As a result, between one quarter and one third of Victoria’s terrestrial plants, birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals, along with numerous invertebrates and ecological communities, are considered threatened.

Native vegetation in this region now

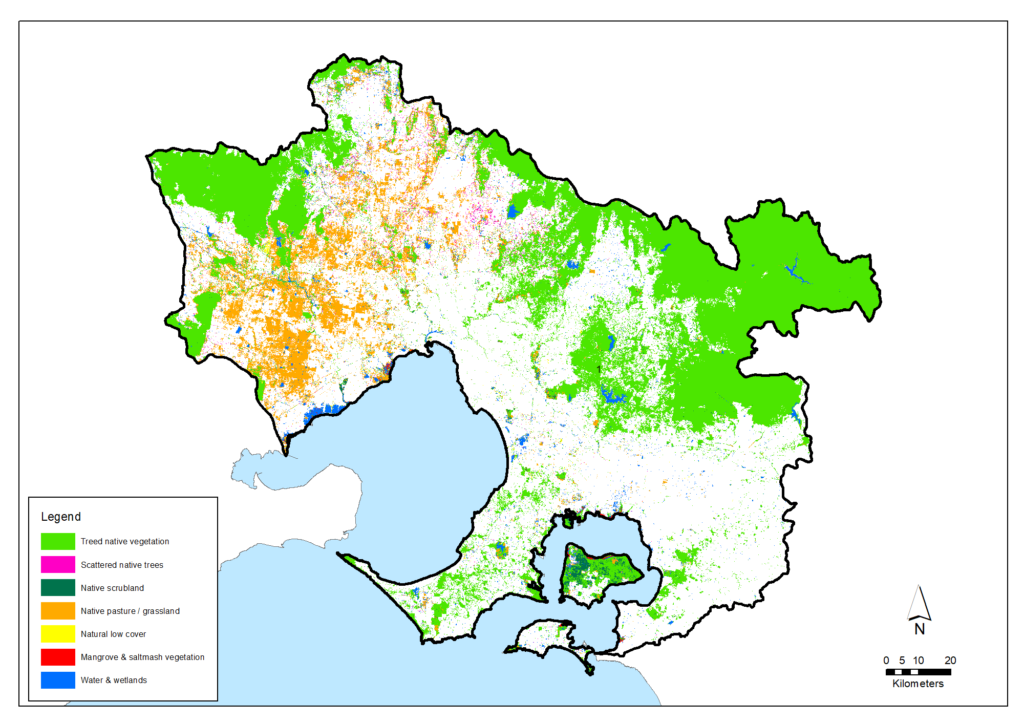

Before European settlement, this region’s approximately 1.278 million hectares of land were covered by diverse vegetation types ranging from rainforest to woodlands, grasslands, heaths and marshes. Today, an estimated 541,812 hectares of native vegetation remains (around 42% of the region). A number of the ecological vegetation classes have been severely depleted in this region including Plains Grassland, Plains Grassy Woodland and Box Ironbark Forest.

Parks Victoria manages by far the largest and most intact of the region’s native vegetation and ecosystems. Parks Victoria’s estate of National, State and Regional Parks and Nature Conservation Reserves comprises 172,600 hectares of land across the Port Phillip & Western Port region.

Estimated extent of native vegetation in the region at 2015-19 (derived from Victorian Land Cover Time Series data)

| Bass Coast, South Gippsland & islands | Casey, Cardinia & Baw Baw | Mornington Peninsula | Yarra Ranges & Nillumbik | Urban Melbourne | Macedon Ranges, Hume, Mitchell & Whittlesea | Melton, Moorabool, Wyndham & Greater Geelong | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treed native vegetation | 14,374 | 59,285 | 16,676 | 186,339 | 14,114 | 47,094 | 66,441 | 404,322 |

| Scattered native trees | 141 | 108 | 198 | 907 | 292 | 5,106 | 1,619 | 8,372 |

| Native scrubland | 3,579 | 553 | 386 | 558 | 1,075 | 480 | 828 | 7,458 |

| Native pasture/grassland | 988 | 1,731 | 1,243 | 1,782 | 3,655 | 25,563 | 56,818 | 91,780 |

| Natural low cover | 212 | 409 | 562 | 351 | 936 | 505 | 1,120 | 4,095 |

| Saltmarsh and mangrove | 1,322 | 390 | 65 | 146 | 268 | 2,190 | ||

| Water and wetlands | 1,788 | 3,496 | 1,520 | 3,040 | 2,069 | 5,258 | 6,424 | 23,595 |

| Total native vegetation (Hectares) | 22,405 | 65,971 | 20,650 | 192,976 | 22,287 | 84,006 | 133,517 | 541,812 |

| Local Area (Hectares) | 84,919 | 237,926 | 72,004 | 264,786 | 145,391 | 221,779 | 251,541 | 1,278,346 |

| Proportion of native vegetation in Local Area | 26% | 28% | 29% | 73% | 15% | 38% | 53% | 42% |

Major challenges and drivers of change

Incremental loss of native vegetation

Over the last 30 years, the extent of native vegetation in the region has reduced by an estimated 23,933 hectares (an average of close to 800 hectares per year) as shown in the table below. The amount of loss has understandably varied across the region depending largely on the vegetation types and the suitability of the land for agriculture and urban development. The reduction has been particularly felt by the native grasslands (generally in the west of the region), scattered trees and areas of water/wetlands, as illustrated in the map below.

Changes in native vegetation in the region over from 1985-90 to 2015-19

Slide toggle to see changes. Click here to view full size in a new window.

| Vegetation class | Estimated extent at 1985-90 (Hectares) | Estimated extent at 2015-19 (Hectares) | Change (Hectares) | Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treed native vegetation | 405,448 | 404,322 | -1,126 | 0% |

| Scattered native trees | 13,805 | 8,372 | -5,433 | -39% |

| Native scrubland | 7,321 | 7,458 | 137 | +2% |

| Native pasture/grassland | 99,827 | 91,780 | -8,046 | -8% |

| Natural low cover | 3,207 | 4,095 | 887 | +28% |

| Saltmarsh and mangrove | 2,098 | 2,190 | 92 | +4% |

| Water and wetlands | 34,040 | 23,595 | -10,445 | -31% |

| Total | 565,745 | 541,812 | -23,933 | -4% |

Melbourne’s population is expected to continue to grow. Urbanisation and population growth in the region’s growth corridors will continue to drive clearing of remnant patches and individual trees.

If this trend from the last 30 years was to continue for the next 30 years, the year 2050 will have seen a reduction of around a further 24,000 hectares. It is acknowledged that there will continue to be losses of native vegetation in some areas due to changing land uses for urban development and agriculture. However, this trajectory is one that the Victorian Government is aiming to avoid by achieving the significant targets for revegetation and new protected areas as outlined in the Biodiversity 2037 plan and reflected at regional scale in this Regional Catchment Strategy.

In peri-urban areas, clearing at the edges of remnant patches and of individual trees will continue for rural subdivisions and landholder amenity. These activities are regulated by the Victorian Government’s guidelines for the removal, destruction or lopping of native vegetation which support an approach of avoiding, minimising and offsetting vegetation losses. However, the losses may not be completely offset by new, improved or more secure vegetation in the same municipality.

When vegetation loss or reduction of quality must occur or is allowed, it is preferred that offsets be established as quickly as possible and be as close as possible to the site of the vegetation loss.

Invasive weeds and disease

Introduced plants and animals are a primary cause of biodiversity decline in all Victorian environments. Although Victoria has implemented some successful programs to control introduced species, there remains a need for sustained on-ground action and biosecurity responses to new and emerging threats.

Invasive weeds are major threats to native vegetation quality. Weed invasions create structural declines in native vegetation and damage their habitat qualities. Weed invasion is the most persistent pressure on the region’s National Parks.

The fungal disease Armallaria and the soil-borne water mould Phytophthora Cinnamomi are widespread in the region. Phytophthora is listed in the world’s top 100 of most invasive species and Victoria’s most significant plant pathogen. It has had serious impacts on vegetation in the Brisbane Ranges, Point Nepean, Mornington Peninsula, Kinglake and Lerderderg Parks.

Pest animals

Populations of various pest animals are a serious issue across the region, including deer, rabbits, pigs and goats. Populations of deer have increased and spread rapidly in the past decade.

Rabbits and deer have a significant impact on native habitat. They alter the composition and structure of native vegetation through browsing. They prevent the regeneration of native plants, spread weeds, cause soil erosion and degrade water quality. They may compete with native herbivores for food, and further degrade the environment by providing an abundant food source for other pests.

The impact of growing feral deer populations is causing particular alarm and has prompted new and coordinated action by community groups such as the Cardinia Deer Management Coalition. Larger-scale coordination is being provided by the Eastern Region Pest Animal Network that was established in 2016 involving 13 Councils in eastern Melbourne and government agencies. The Network has published the Eastern Region Pest Animal Strategy 2020-2030. The strategy aims to protect defined assets by overcoming 12 barriers to better pest animal control including:

- The need to adapt pest control to specific landscapes

- Lack of knowledge about how and where pests disperse across this region’s landscapes

- The need to maintain consistent, long-term control to prevent re-invasions

- The need for persistent and coordinated action across all land tenures

- Community perceptions about animal welfare, protection and varying affections for feral and native animals

- Impact of control methods on domestic animals and animal ethics/welfare

- Legal constraints (for example, deer are currently protected under the Wildlife Act 1975)

- The need for principled cost-sharing for adequate and sustained funding

- The need to rationalise the wide range of monitoring methods used for different pest species

- Lack of a single government body responsible for deer control.

Changed fire regimes and frequency

Bushfire control and prevention works are essential to reduce risks to the health, safety and assets of the Victorian community. Depending on their frequency and type, fires, including planned burning, can have significant positive or negative effects on biodiversity. Negative impacts on biodiversity can occur when fires are too frequent, intensive or extensive for recovery to occur. Victoria’s risk-based and community-focused approach to fire planning aims to find an appropriate balance between the risk to humans and infrastructure, and to environmental values.

A drier future climate will create the risk of more frequent and severe wildfire. The Victorian Climate Change Adaptation Program predicts that, in the Port Phillip & Western Port region, the number of ‘extreme’ fire danger days is expected to increase by between 20 per cent and 135 per cent by 2050. Many species have adaptations that allow them to survive fire. However the Victorian Climate Change Adaptation Plan highlights that some vulnerable ecosystems are at risk.

Climate change and sea-level rise

Climate change is expected to amplify existing pressures on native vegetation by exposing it to:

- Increased long-term average temperatures

- Increased hot-day temperatures

- Lower and more erratic rainfall

- Higher evaporation

- Lower soil moisture

- Increased fire-weather frequency and intensity.

- Sea level rise.

Coastal vegetation on Port Phillip Bay and Western Port is vulnerable to sea level rise. Shrinking coastal margins will make protecting coastal vegetation difficult, particularly where housing, roads and other developments compete for coastal land.

Climate change will exacerbate environmental pressures such as drought, wildfire, weeds and pest animals on natural habitats and biodiversity. Climate change is likely to be making obsolete and perilous the trade-offs between development and conservation used in previous ‘balanced decision-making’.

Incremental damage

Incremental widespread damage such as illegal clearing, recreation, vandalism, informal vehicle tracks, firewood collection, rubbish dumping are ongoing pressures on native vegetation from large and growing populations.

Policy and planning

Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037 is the Victorian Government’s plan for the future of Victoria’s biodiversity. The plan sets the ambitious but achievable task of stopping the decline of our biodiversity and pursuing a long-term pathway for the overall improvement of biodiversity. Biodiversity 2037 also sets goals for ‘Victorians Valuing Nature’ which aim to increase community awareness and understanding and encourage more Victorians to enjoy our natural environment and participate in caring for biodiversity.

The Biodiversity 2037 plan establishes state-wide aims including:

- A net gain in the overall extent and condition of habitats across terrestrial, waterway and marine environments

- No vulnerable or near-threatened species will become endangered

- All critically endangered and endangered species will have at least one option available for being conserved ex situ or re-established in the wild should they need it

- 200,000 hectares of new permanently protected areas on private land

- 200,000 hectares of revegetation in priority areas for connectivity between habitats

- 4 million hectares of control of pest herbivores (e.g. deer, rabbits, goats, feral horses) in priority locations

- 1.5 million hectares of weed control in priority locations.

Priorities for achieving these targets across Victoria are identified by the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action and presented using NaturePrint and Strategic Management Prospects and Biodiversity Response Planning. Mapping can be explored at the NatureKit website.

For the Port Phillip and Western Port region, this Regional Catchment Strategy establishes our regional targets and priorities that will contribute to achieving the statewide aims. It also identifies projects that can make tangible gains and which can be implemented by the many organisations, community groups and individual land managers involved in native vegetation management across this region.

Other strategies and plans will also contribute to the protection, enhancement and expansion of native vegetation in this region including the Victorian Government’s blueprint for managing Melbourne’s open spaces – Open Space for Everyone Strategy, Trust for Nature’s Statewide Conservation Plan and the Living Melbourne: our metropolitan urban forest strategy with the aim to improve Melbourne’s greenery across the city and its suburbs. Parks Victoria is using the internationally recognised Conservation Action Planning method to make strategies that will help it improve the health of ecosystems in the region’s National, State and Regional Parks. The Eastern Region Pest Animal Network has also published the Eastern Region Pest Animal Strategy 2020-2030.

At a local level, council plans and municipal biodiversity plans are also particularly important to guide the substantial native vegetation management programs led or commissioned by councils. Alongside the role of councils, it is important for the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action to consider local and regionally significant species when reviewing planning applications for the removal of native vegetation and fauna species habitats.

Biodiversity management is also part of a broader aim to ensure all natural resources are managed in a coordinated and integrated way. Outlining this approach, the Victorian Government’s Our Catchments Our Communities: Building on the Legacy for Better Stewardship statement particularly encourages ‘catchment stewardship’ – achieving public benefit (adding environmental, economic, cultural and social value) and going beyond basic duty of care to leave our natural resources in better condition than their current state.

Traditional Owners are the voice of their Country

For all policy and planning, there is a need for recognition and inclusion of Traditional Owner knowledge and aspirations (see target 13.1). The water and lands are increasingly being recognised as ‘living and integrated natural entities‘ and the Traditional Owners should be recognised as the ‘voice of these living entities’. Country Plans will describe the vision and priorities of the Traditional Owners for Country in line with their roles as Registered Aboriginal Parties, and will provide a strong basis for all planning to recognise and include the voice of these Traditional Owners.

Targets for establishing new permanently protected areas of native vegetation and open space

New parks

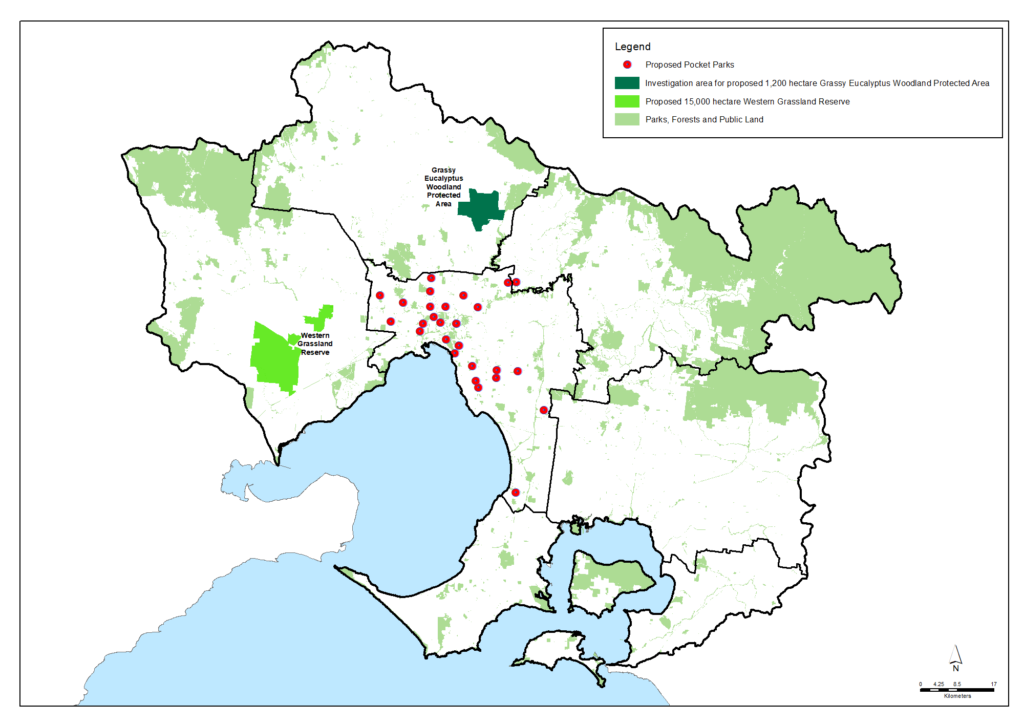

Permanent protection, such as within parks and reserves on public land and in conservation covenants on private land, is the most effective means of securing the extent of native vegetation for the future. In regard to adding new parks into the public land estate, priorities include the establishment by the Victorian Government of the following new parks:

- 15,000 hectares of a new Western Grassland Reserve

- 1,200 hectares of a new Grassy Eucalypt Woodland Protected Area

- 6,500 hectares of new suburban parks providing green spaces in Melbourne’s growing outer suburbs including parkland, trails, pocket parks and off-leash dog parks.

However, it should be noted that the establishment of the Western Grassland Reserve and the Grassy Eucalypt Woodland Protected Area was committed to by the Victorian Government in 2010 associated with the Melbourne Strategic Assessment to offset native vegetation lost due to development in Melbourne’s extended urban growth boundary. This commitment has enabled extensive clearing of the native vegetation and fauna habitat, so it is imperative that the reserves are established as soon as possible.

In addition to the existing Government commitments, opportunities to secure additional important native vegetation in new parks and reserves are encouraged in order to improve native habitat across the region. These might include large areas that provide opportunity for extensive patches of vegetation communities and plant species to be preserved or re-created, or small patches that are important havens for local communities or protect remnants of native species.

An example of an opportunity is a sub-division in Riddells Creek known as ‘Barrm Birrm’ (place of many yam roots) which has high quality woodlands in private and Council ownership. The 100+ hectare site was subdivided into small allotments in the 1880s with the land now owned by approximately 130 different landowners. The site contains native vegetation of high conservation significance on the south east side of the Macedon Ranges including native orchids and the only plant endemic to the Macedon Ranges Shire – the Hairy-leaf Triggerplant. The site plays an important landscape connectivity role, adjoining public land at Conglomerate Gully Reserve and providing habitat links through to T Hill Flora Reserve and Mount Charlie Reserve. Due to the site’s natural values, high fire risk and lack of services, the land is not considered to be suitable for development and current planning controls prevent development. The Council operates a “gift back” scheme to encourage the transfer of private land parcels to Council but this is process is slow and relies on the voluntary participation of landowners. A more efficient and effective mechanism may be for government to acquire the land enabling integration into the adjoining public reserve system.

Progress toward the target below will be monitored primarily using information developed and published by the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action and Parks Victoria.

Target 5.1 – New parks

By 2027

At least 6,500 hectares of new suburban parks established in the region between 2021 and 2027.

By 2037

At least 15,000 hectares of a new Western Grassland Reserve and 1,200 hectares of a new Grassy Eucalypt Woodland Protected Area established in this region.

By 2050

Significant areas of additional new parks established across this region providing improved security, extent and quality of native habitat.

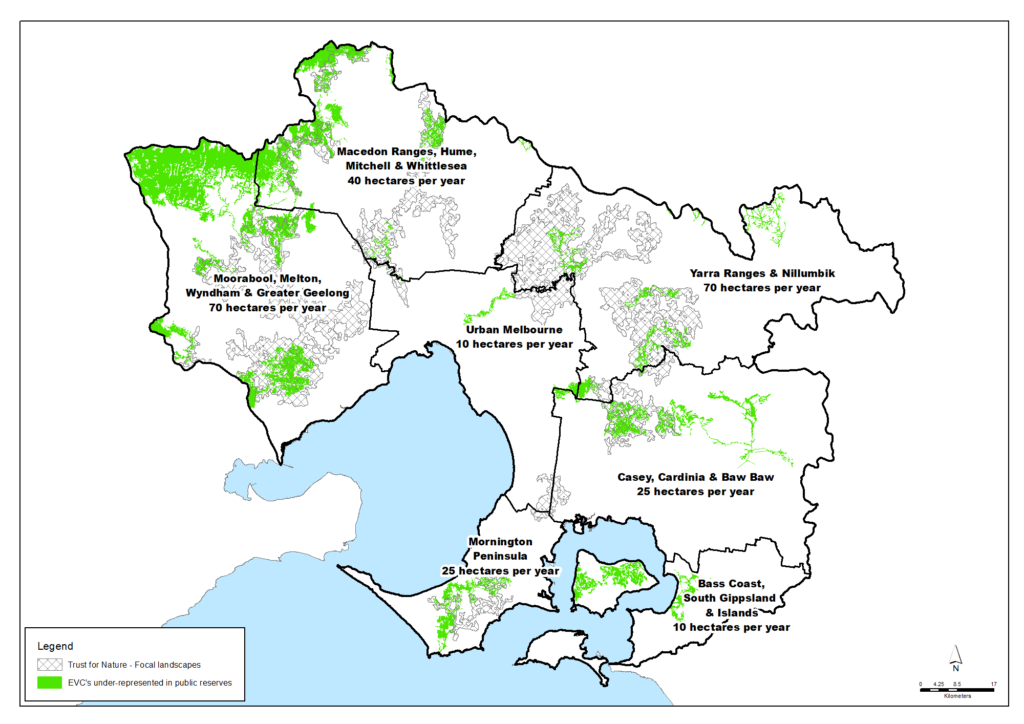

Permanent protection of vegetation on private land

Permanent protection of vegetation and habitats on private land can be achieved in ways such as voluntary protection covenants placed on land titles. The Victorian Government’s biodiversity plan, Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037, sets a state-wide target for 200,000 hectares of new, permanently protected areas on private land by 2037.

The Port Phillip & Western Port region’s contribution to this target is proposed to be 5,000 hectares by 2037. An average of 250 hectares would need to be protected each year to reach this target. This rate of protection would secure at least 8,250 hectares of high-value vegetation on private land by 2050.

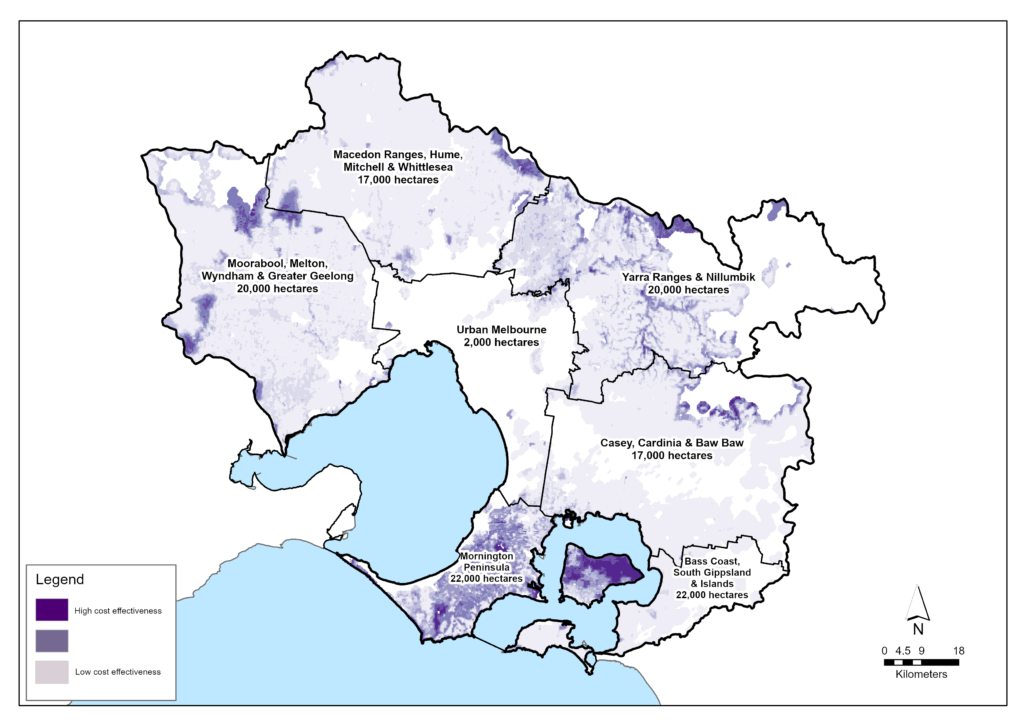

The map below shows:

- How the average annual target might be shared across the region’s seven Local Areas. Current conservation activity suggests these nominal amounts are realistic and sustainable.

- Where new protected areas of private land could best meet the Trust for Nature’s Statewide Conservation Plan priorities to secure ecological vegetation classes (EVCs) that are under-represented in public reserves.

Progress toward this target will be monitored primarily using information from Trust for Nature.

Target 5.2 – Permanent protection

By 2027

At least 2,500 hectares of new permanently protected vegetation areas established on private land in this region between 2017 and 2027 (an average of at least 250 hectares per year).

By 2037

At least 5,000 hectares of new permanently protected vegetation areas established on private land in this region between 2017 and 2037 (an average of at least 250 hectares per year).

By 2050

At least 8,250 hectares of new permanently protected vegetation areas established on private land in this region between 2017 and 2050 (an average of at least 250 hectares per year).

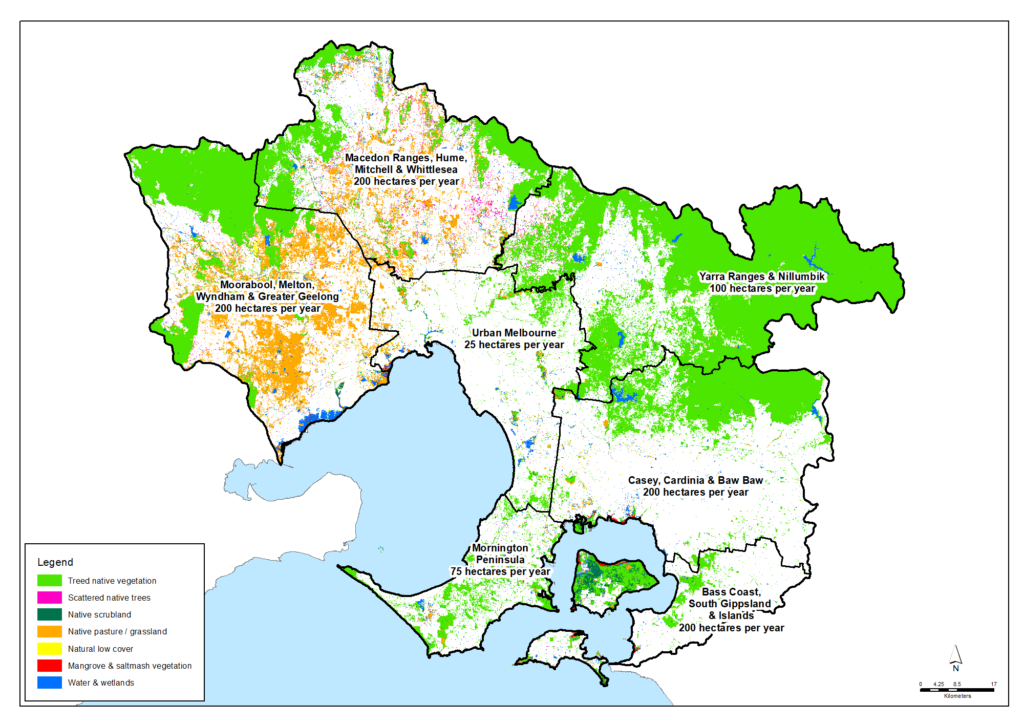

Targets for revegetation and biolinks

Revegetation remains a vital means of countering vegetation losses and restoring and expanding the amount of native vegetation in this region.

Of the state-wide target of 200,000 hectares of revegetation from 2017-2037, this region’s contribution is proposed to be at least 20,000 hectares in priority areas, corresponding to an average of 1,000 hectares per year. Continuing this level of achievement beyond 2037 would see at least 33,000 hectares of revegetation established between 2017-2050.

Target 5.3 – Revegetation

By 2027

At least 10,000 hectares of revegetation established in priority areas for habitat connectivity in this region between 2017 and 2027 (an average of at least 1,000 hectares per year).

By 2037

At least 20,000 hectares of revegetation established in priority areas for habitat connectivity in this region between 2017 and 2037 (an average of at least 1,000 hectares per year).

By 2050

At least 33,000 hectares of revegetation established in priority areas for habitat connectivity in this region between 2017 and 2050 (an average of at least 1,000 hectares per year).

The regional target of 1,000 hectares of revegetation per year could be achieved with contributions across the region such as those outlined below. These are nominal targets for each Local Area, but are considered to be realistic and sustainable.

Progress toward this target will be monitored using data collated by the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action. This may be supplemented by annually asking key natural resource management organisations in the region such as Councils, water corporations, Parks Victoria, relevant government departments and Landcare networks/groups for the amount of revegetation they have undertaken or commissioned.

The establishment of new native vegetation can be beneficial and is encouraged for many locations including in suburban gardens, on farms and rural properties, on public land and riversides, and in new urban developments.

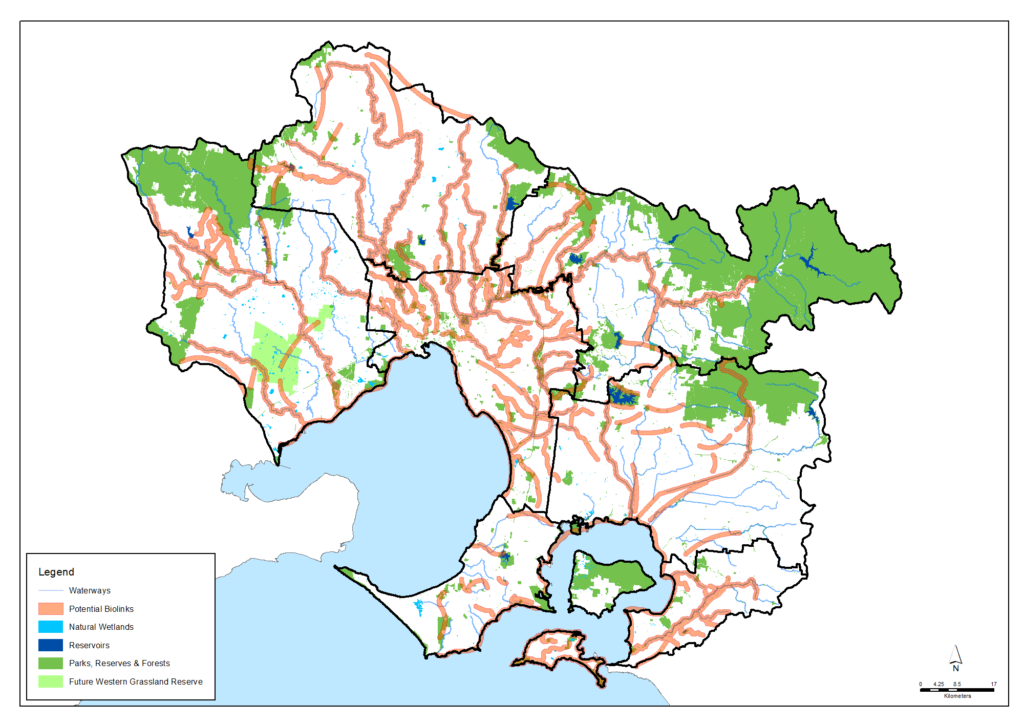

However, the priority for major revegetation programs is the establishment of significant biolinks across the region’s landscapes that create connections between existing habitat, enable species transit and improve ecosystem resilience to climate change and habitat fragmentation. Along with biodiversity benefits, major revegetation programs will sequester carbon from the atmosphere and therefore help to achieve net zero carbon emissions. Similarly, opportunities for capture and storage of ‘blue carbon’ in the wetland, coastal, estuarine and marine habitat of the region could have multiple benefits.

Target 5.4 – Major new biolinks

2021

Planning or work is underway to create numerous biolinks of varying scales at locations across the region.

By 2028

Significant revegetation programs have been undertaken from 2021 to 2028 and are contributing to the creation of biolinks in priority locations across the region.

By 2050

Significant, sustained revegetation programs have been undertaken from 2021 to 2050 and have created numerous major biolinks in priority locations across the region.

A number of major potential biolinks are illustrated below. They include potential biolinks identified from existing strategies and plans by Councils, Government agencies, community groups and collaborations. For more detail about each potential biolink, explore the biolinks layer in the Regional Map.

The boundaries of the potential biolinks are not intended to be precise as their pathways, width and specific revegetation sites need to be worked out with many individual landholders, but they are recognised as having strong potential for revegetation and other activities to improve large-scale connectivity or create ‘habitat stepping stones’ between and around existing vegetation.

Targets for maintaining and enhancing vegetation quality

The quality of the existing native vegetation in this region is impacted by numerous threats, the most widespread and serious being weeds and pest animals. Tailored and sustained pest management programs are therefore vital in priority locations across the region.

Of the state-wide targets of 4 million hectares of sustained pest herbivore control (e.g. deer, rabbits, goats, pigs, horses) and 1.5 million hectares of sustained weed control in priority locations from 2017-2037, this region’s contribution is proposed to be at least 120,000 and 40,000 hectares respectively.

The aspirational aim for this region is to achieve and sustain this level of control immediately and continue it through to 2037 and then to 2050.

Target 5.5 – Pest and weed control

By 2027

Sustained pest herbivore control achieved for at least 120,000 hectares in priority areas, and sustained weed control achieved for at least 40,000 hectares in priority areas of this region from 2017 to 2027.

By 2037

Sustained pest herbivore control maintained for at least 120,000 hectares in priority areas, and sustained weed control maintained for at least 40,000 hectares in priority areas of this region through to 2037.

By 2050

Sustained pest herbivore control maintained for at least 120,000 hectares in priority areas, and sustained weed control maintained for at least 40,000 hectares in priority areas of this region through to 2050.

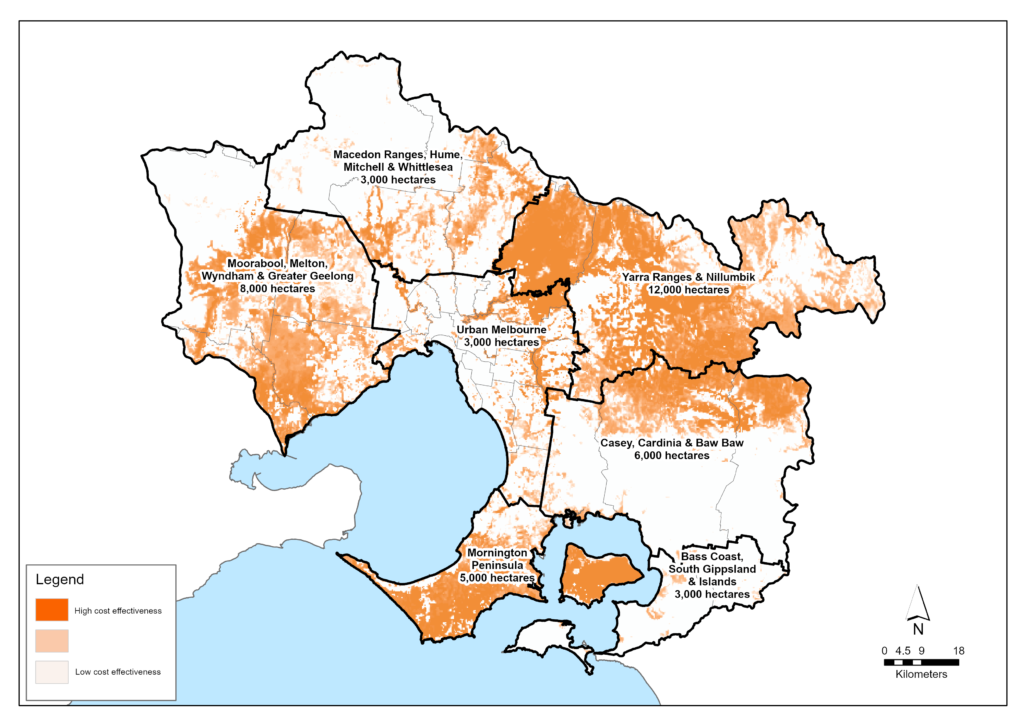

While pest control work to protect and enhance native vegetation quality will be valuable all across the region, strategic priorities have been identified through the Victorian Government’s Strategic Management Prospects and Biodiversity Response Planning processes coordinated by the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action. The maps below summarise priorities with further detail available at the NatureKit website.

The aspirational regional targets could be achieved with contributions across the region such as those outlined below. These are nominal targets for each Local Area.

Progress toward this target will be monitored using data collated by the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action. This may be supplemented by annually asking key natural resource management organisations in the region such as councils, water corporations, Parks Victoria, relevant Government Departments and Landcare networks/groups for the amount of pest control work they have undertaken or commissioned.

Priorities for threatened vegetation

Threatened species and ecological communities are considered to be priorities for protection and recovery work. In most circumstances, work to protect and enhance threatened flora species and ecological communities will also benefit other native species, flora communities and a diverse range of native animal species that rely on this habitat.

A review of Victoria’s threatened species list was completed by the former Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning in 2021 (now Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action). An estimated 333 species of native vegetation and 24 ecological communities that are known to recently occur in this region are listed as threatened. Some of those are identified in the table below. More detailed lists of threatened species are available at the Data tables page of this strategy and at the Victorian threatened species list.

Some of the threatened flora species and ecological communities known to occur in the region

| Species | Scientific name | FFG Conservation Status | EBPC Conservation Status | Bass Coast, South Gippsland & islands | Casey, Cardinia & Baw Baw | Mornington Peninsula | Yarra Ranges & Nillumbik | Urban Melbourne | Macedon Ranges, Hume, Mitchell & Whittlesea | Melton, Moorabool, Wyndham & Greater Geelong | Port Phillip Bay | Western Port |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Button Wrinklewort | Rutidosis leptorhynchoides | Endangered | Endangered | X | X | X | ||||||

| Buxton Gum / Silver Gum | Eucalyptus crenulata | Endangered | Endangered | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Charming Spider-orchid | Caladenia amoena | Critically endangered | Endangered | X | ||||||||

| Christmas Spider-orchid | Caladenia flavovirens | Critically endangered | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Coast Helmet-orchid | Corybas despectans | Endangered | X | X | ||||||||

| Frankston Spider-orchid | Caladenia robinsonii | Critically endangered | Endangered | X | X | X | ||||||

| Kilsyth South Spider-orchid | Caladenia sp. aff. venusta (Kilsyth South) | Critically endangered | Critically Endangered | X | ||||||||

| Large-flower Crane's-bill | Geranium sp. 1 | Critically endangered | X | X | X | |||||||

| Leafy Greenhood | Pterostylis cucullata | Vulnerable | X | X | ||||||||

| Little Pink Spider-orchid | Caladenia rosella | Critically endangered | Endangered | X | ||||||||

| Matted Flax-lily | Dianella amoena | Critically endangered | Endangered | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Purple Diuris | Diuris punctata var. punctata | Endangered | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Round-leaf Pomaderris | Pomaderris vacciniifolia | Critically endangered | Critically Endangered | X | X | X | ||||||

| Salt Paperbark | Melaleuca halmaturorum | Endangered | X | |||||||||

| Slender Tree-fern | Cyathea cunninghamii | Critically endangered | X | X | ||||||||

| Spiny Rice-flower | Pimelea spinescens subsp. spinescens | Critically endangered | Critically Endangered | X | X | X | ||||||

| Strzelecki Gum | Eucalyptus strzeleckii | Critically endangered | Vulnerable | X | X | |||||||

| Sunshine Diuris | Diuris fragrantissima | Critically endangered | Endangered | X | X | |||||||

| Swamp Everlasting | Xerochrysum palustre | Critically endangered | Vulnerable | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Tall Astelia | Astelia australiana | Endangered | Vulnerable | X | X | |||||||

| White Sunray / Hoary Sunray | Leucochrysum albicans subsp. tricolor | Endangered | Endangered | X |

| Ecological community | FFG Conservation Status | EPBC Conservation Status | Bass Coast, South Gippsland & islands | Casey, Cardinia & Baw Baw | Mornington Peninsula | Yarra Ranges & Nillumbik | Urban Melbourne | Macedon Ranges, Hume, Mitchell & Whittlesea | Melton, Moorabool, Wyndham & Greater Geelong | Port Phillip Bay | Western Port |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpine Sphagnum Bogs and Associated Fens | Endangered | X | X | ||||||||

| Giant Kelp Marine Forests of South East Australia | Endangered | X | X | ||||||||

| Grassy Eucalypt Woodland of the Victorian Volcanic Plain | Critically endangered | X | X | X | |||||||

| Grey Box (Eucalyptus microcarpa) Grassy Woodlands and Derived Native Grasslands of South-eastern Australia | Endangered | X | X | X | |||||||

| Natural Damp Grassland of the Victorian Coastal Plains | Critically endangered | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Natural Temperate Grassland of the Victorian Volcanic Plain | Critically endangered | X | X | X | |||||||

| Seasonal Herbaceous Wetlands (Freshwater) of the Temperate Lowland Plains | Critically endangered | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Subtropical and Temperate Coastal Saltmarsh | Vulnerable | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| White Box-Yellow Box-Blakely's Red Gum Grassy Woodland and Derived Native Grassland | Critically endangered | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Central Gippsland Plains Grassland | Threatened | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Coastal Moonah Woodland | Threatened | X | X | ||||||||

| Cool Temperate Mixed Forest | Threatened | X | X | X | |||||||

| Cool Temperate Rainforest | Threatened | X | X | X | |||||||

| Forest Red Gum Grassy Woodland | Threatened | X | X | X | |||||||

| Grey Box - Buloke Grassy Woodland Community | Threatened | X | X | X | |||||||

| Herb-rich Plains Grassy Wetland (West Gippsland) | Threatened | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Limestone Grassy Woodland | Threatened | X | X | X | |||||||

| Port Phillip Bay Entrance Deep Canyon Marine Community | Threatened | X | |||||||||

| Rocky Chenopod Open Scrub | Threatened | X | X | X | |||||||

| San Remo Marine Community | Threatened | X | |||||||||

| Sedge-rich Eucalyptus camphora Swamp | Threatened | X | |||||||||

| South Gippsland Plains Grassland | Threatened | X | X | X | |||||||

| Western (Basalt) Plains Grasslands | Threatened | X | X | X | |||||||

| Western Basalt Plains (River Red Gum) Grassy Woodland | Threatened | X | X | X |

Target 5.6 – Threatened vegetation

2021

333 native vegetation species and 24 ecological communities occurring in this region are listed as threatened.

By 2028

All threatened native vegetation species and ecological communities in the region are retained and have positive trajectories for their extent, health and resilience.

By 2050

All threatened native vegetation species and ecological communities in the region are retained and are self sustainable, secure, healthy and resilient.

Progress toward this target will be monitored primarily using information developed and published by the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action.

Partner organisations

The following organisations formally support the pursuit of the visions and targets for native vegetation. They have agreed to provide leadership and support to help achieve optimum results with their available resources, in ways such as:

- Fostering partnerships and sharing knowledge, experiences and information with other organisations and the community

- Seeking and securing resources for the area and undertaking work that will contribute to achieving the visions and targets

- Assisting with monitoring and reporting on the condition of the area.

Victorian Government

- Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA)

- Melbourne Water

- Parks Victoria

- Phillip Island Nature Parks

- Victorian Environmental Water Holder

- Trust for Nature

- Victorian Planning Authority

- Environment Protection Authority Victoria (EPA)

- Sustainability Victoria

- Westernport Water

- Zoos Victoria

Local Government

- Hume City Council

- Macedon Ranges Shire Council

- City of Greater Geelong

- Brimbank City Council

- Monash City Council

- Glen Eira City Council

- Bayside City Council

- City of Melbourne

- City of Port Phillip

- Kingston City Council

- Maroondah City Council

- City of Casey

- Cardinia Shire Council

- Baw Baw Shire Council

- Bass Coast Shire Council

- South East Councils Climate Change Alliance

- City of Whittlesea

- Wyndham City

- Moorabool Shire Council

- Hobsons Bay City Council

- Moonee Valley City Council

- City of Greater Dandenong

- Whitehorse City Council

- City of Stonnington

- Knox City Council

- South Gippsland Shire Council

- Eastern Region Pest Animal Network

- Western Alliance for Greenhouse Action

- Northern Alliance for Greenhouse Action

- Eastern Alliance for Greenhouse Action

Traditional Owners

- Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation

- Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation

Non Government

- The Nature Conservancy

- Conservation Volunteers Australia

- Gardens for Wildlife Victoria

- Mt Rothwell Biodiversity Centre / Odonata

- The People and Parks Foundation

- Field Naturalists Club of Victoria

- Victorian National Parks Association

- Native Fish Australia (Vic)

- OzFish Unlimited

- Birdlife Australia

- Victoria Walks

- Western Port Seagrass Partnership

- Habitat Restoration Fund

Community

- Port Phillip EcoCentre

- Werribee River Association

- Friends of Lower Kororoit Creek Inc

- NatureWest

- Little River Community Landcare Inc

- Federation for Environment and Horticulture in the Macedon Ranges

- Upper Deep Creek Landcare Network

- Jacksons Creek EcoNetwork

- Greening of Riddell

- Friends of Emu Bottom Wetlands Reserve

- Friends of Daly Nature Reserve

- Deep Creek Landcare Group

- Riddells Creek Landcare Group

- Newham and District Landcare Group

- Merri Creek Management Committee

- Darebin Creek Management Committee

- Yarra Ranges Landcare Network

- Middle Yarra Landcare Network

- Northern Yarra Landcare Network

- Nillumbik Landcare Network

- Friends of Dandenong Valley Parklands

- Nangana Landcare Network

- Johns Hill Landcare Group

- Gippsland Threatened Species Action Group

- Yarra Riverkeeper Association

- Mornington Peninsula Landcare Network

- Merricks Coolart Catchment Landcare Group

- Red Hill South Landcare Group

- Sheepwash Creek Catchment Landcare Group

- Manton and Stony Creeks Landcare Group

- Main Creek Catchment Landcare Group

- Cardinia Environment Coalition

- Bass Coast Landcare Network

- Bass Valley Landcare Group

- French Island Landcare Group

- South Gippsland Landcare Network

- Loch-Nyora Landcare Group

- Mt. Lyall Landcare Group

- Poowong & District Landcare Group

- Triholm Landcare Group

- Kooyongkoot Alliance

- Friends of Olinda Creek

- Abbotsford Riverbankers Inc

- Mornington Peninsula Koala Conservation

- Phillip Island Landcare Group

- Western Port Catchment Landcare Network

- Westernport Swamp Landcare Group

Add your organisation as a supporter and partner

If your organisation supports these directions and targets for native vegetation and wishes to be listed as a partner organisation, you can request to be listed as a partner organisation. Adding your organisation to this list will:

- Enable your organisation to list one or more priority projects in the Prospectus which will describe how your priority project will pursue the targets of this Regional Catchment Strategy and potentially make your organisation’s project more attractive to investors by using the strategy to highlight its relevance and value

- Demonstrate your commitment to a healthy and sustainable environment

- Demonstrate the level of community engagement and support for this work.

Priority projects to move forward

Priority projects

There are significant ongoing programs and initiatives undertaken by many organisations in this region that are vital for protecting and enhancing native vegetation and are priorities to continue. These include programs led by Councils, Melbourne Water, Parks Victoria, the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action, community groups and non-Government organisations.

In addition, there are numerous project proposals that, if funded and implemented, can contribute to achieving the Regional Catchment Strategy’s visions and targets for native vegetation. Project proposals include:

- Permanently Protecting Melbourne Habitat led by Trust for Nature

- Western Grasslands Reserve Program led by Parks Victoria

- Good Neighbour Program led by Parks Victoria

- Peri-urban Deer Program led by Parks Victoria and Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA)

- Peri-urban Weed Program led by Parks Victoria and Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA)

- Pyrete Ranges to Long Forest Biolink proposed by Melbourne Water as part of the Grow West program

- Connecting the Dots – Buloke Protection proposed by Melbourne Water as part of the Grow West program

- Biolinks for the Brush-tailed Phascogale proposed by Melbourne Water as part of the Grow West program

- Living Links Partnership proposed Melbourne Water as part of the Living Links program

- Rivers to Ranges led by the Nillumbik Shire Council

- Northern Yarra Weed Action led by the Northern Yarra Landcare Network

- Woori Yallock Creek Vegetation Improvement proposed by Melbourne Water

- Green’s Bush to Arthurs Seat Biolink led by the Mornington Peninsula Landcare Network

- Arthurs Seat Habitat Restoration led by Sheepwash Creek Catchment Landcare Group

- Main Creek Landcare Karamu Eradication Project proposed by the Main Creek Catchment Landcare Group

- Cannibal Creek Catchment Biodiversity Project proposed by the Western Port Catchment Landcare Network

- Tarago Catchment Project proposed by the Western Port Catchment Landcare Network

- Forest Health Monitoring – Nillumbik led by the Nillumbik Landcare Network

- Healesville to Phillip Island Nature Link led by Healesville to Phillip Island Nature Link

- Peaks to Plains: Enhancing the You Yangs and grasslands proposed by Melbourne Water

- Deep Creek Biolink proposed by Upper Maribyrnong Catchment Group

- Merri Creek Biolink led by Merri Creek Management Committee

- Cobaw Biolink led by the Newham and District Landcare Group

- Significant plants of the Brisbane Ranges proposed by the Melbourne Water

- Skeleton Mudflats Reserve – Regeneration led by NatureWest

- Werribee – Little River Biosites Restoration proposed by Nature West

- Growing Grassy Woodlands proposed by the Macedon Ranges Shire Council

- Will-im-ee Moor-ing Biolink proposed by the Macedon Ranges Shire Council

- Permanent protection for Barrm Birrm proposed by the Macedon Ranges Shire Council

- Jacksons and Riddells Creeks Wildlife Corridor – proposed by Jacksons Creek EcoNetwork

- Jacksons Creek & Emu Bottom Wetland Rabbit Control – proposed by Melbourne Water

- Sydenham Park led by Brimbank City Council

- Maribyrnong Valley Connection proposed by the Hume City Council

- Ensuring the survival of Temperate Grasslands and Grassy Woodlands proposed by the Hume City Council

- Elsternwick Park led by Bayside City Council

- Port Phillip Wildlife Corridors led by the City of Port Phillip

- Growing Dandenong Biodiversity led by the City of Greater Dandenong

- Linking the Mornington Peninsula Landscape led by the Mornington Peninsula Landcare Network

- Balnarring to the Bay Biolink led by Merricks Coolart Catchment Landcare Group

- Bass Coast Biodiversity Biolinks led by the Bass Coast Shire Council

- Cardinia Creek catchment enhancement proposed by the Southern Ranges Environment Alliance

- North Western Port Nature Conservation Reserve Terrestrial Herbivore Management proposed by Parks Victoria

- North Western Port Nature Conservation Reserve Weed Control proposed by Parks Victoria

- Reef Island and Bass River Mouth Nature Conservation Reserve Terrestrial Herbivore Management proposed by Parks Victoria

- Western Port Intertidal Coastal Reserve Terrestrial Herbivore Management proposed by Parks Victoria

- Point Nepean National Park Weed Control proposed by Parks Victoria

- French Island National Park Terrestrial Herbivore Management proposed by Parks Victoria

- French Island National Park Weed Control proposed by Parks Victoria

- Mornington Peninsula National Park Weed Control proposed by Parks Victoria.

A list of project proposals and their key details can be viewed on the Prospectus section of this website.

Propose a new priority project

As part of the ongoing development and refinement of this Regional Catchment Strategy, additional priority projects may be considered for inclusion in the Prospectus.

If your organisation supports the directions and targets for native vegetation and has a project it would like highlighted and supported in this Regional Catchment Strategy, please submit a project proposal.